Are Emotional Needs of Physical Trauma Victims Being Ignored?

*This is an article from the Summer 2021 issue of Combat Stress

By Chaplain LTC (Ret) David J. Fair, PhD, CTS, FAIS

“A broken bone will heal in a couple weeks, but a broken spirit can last a lifetime.”

Geoffrey Holsclaw

Northern Seminary

As a First Responder (Crisis) Chaplain, I recently had a revelation, which came after comforting a critically injured man and consoling his distraught family. As the helicopter lifted off with the victim being rushed to a trauma center, his parents and daughter began the long 200-mile road trip. I could not help but wonder, “what now?” I knew the man’s physical injuries would be addressed, but what about the injury to his soul? What about the psychological wellbeing of his family?

Since the late 1980’s, much has been done to alleviate the emotional suffering of emergency service responders. In more recent years, Crisis Intervention Models were developed out of which came useful tools such as Critical Incident Stress Debriefings, Defusings, and one-on-one crisis intervention are being used more widely in the private sector.1 Police, Fire, and EMS workers no longer must hide their pain. Witnesses to school shootings, mass casualties, and both manmade and natural disasters are being provided in a more widespread manner. These crisis intervention models and tools (such as Critical Incident Stress Management commonly referred to as CISM2) are often utilized in conjunction with Psychological First Aid in a mass casualty event.

In mass casualty events, Chaplains typically have two groups to which they may be deployed. The first will be those first responders working the disaster (I will use disaster and mass casualty interchangeably). The second group will be those actual victims of the disaster. It would be this group that the crisis intervention model of psychological first aid would be employed.

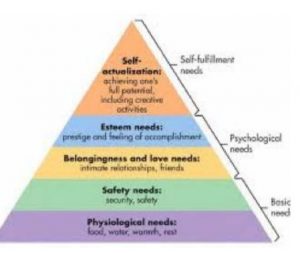

Abraham Maslow was a 20th century American psychologist who was best known for creating Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, a theory of psychological health predicated on fulfilling innate human needs in priority, culminating in self-actualization.

Under Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, the human mind must meet basic physiological needs (food, water, shelter, safety, security) before psychological needs (intimacy, relationship, friends, self-esteem).

In a disaster such as an earthquake or tornado, which literally tears a town to rubble, a chaplain may be deployed and asked to assist the victims of the disaster. If we look at Maslow’s hierarchy of needs as a chaplain, prayer is not what the victim’s immediate needs would be. Victims are going to be concerned with obtaining shelter, safety, water, food, family members. This will be the number one focus because under Maslow’s theory, motivation is driven by deficits. Victims deficits in a disaster are meeting basic needs. Psychological First Aid, such as the program offered by National Child Traumatic Stress Network (see https://learn.nctsn.org), is a developed set of skills which help meet disaster victims’ basic needs. The goal is stabilization of victims by providing for their basic needs. It is only after that when the victims can concern themselves with other higher levels under Maslow’s theory.

Little is being said about meeting the same psychological needs of people who have been injured physically. It may be because we think hospital social workers are meeting these needs. After spending some 25 years as a chaplain I know firsthand the nature of people’s emotional needs. Social workers have their hands full with logistics and paperwork and so few referrals to psychologists or psychiatrists are being made.

It is not because no one wants to help people bearing both physical and emotional scars. It is the old saying, “out of sight, out of mind.” Doctors order CT scans and MRI’s, but there is no device which can X-ray the soul. There may be some cursory comments made to the victim to breathe deeply and relax, but there are no clear-cut interventions to begin the process of healing traumatic memories and psychological injuries.

It is not because no one wants to help people bearing both physical and emotional scars. It is the old saying, “out of sight, out of mind.” Doctors order CT scans and MRI’s, but there is no device which can X-ray the soul. There may be some cursory comments made to the victim to breathe deeply and relax, but there are no clear-cut interventions to begin the process of healing traumatic memories and psychological injuries.

Of course, there are priorities: start the breathing, stop the bleeding, and with the hustle and tussle of the emergency department, there is little time for anything else before the next case comes along. Then, with managed care restrictions and denials of care, the patient is hurried out of the facility in a few days to recuperate at home.

Then we turn to home and the patient’s family. What about the family? They are dealing with the emotional turmoil of their loved one’s injuries and probable lifestyle changes. They may also be dealing with the stress of fearing that their loved one was going to die. We prepare family members of emergency workers in helping their families deal with the psychological aftermath, but what if anything is being done for the families of injury victims?

I have yet to see any discharge orders telling the patient what to do for their emotional well-being. To be sure, there are advocates, such as Victim Assistance4 personnel, who will see to it that rape victims receive necessary counseling, and victim service coordinators will frequently inform crime victims of what services are available.

Yet, for the trauma victim of a fiery car crash, a severed body part or similar tragedy, precious little is being done to relieve their emotional suffering. They are left to fend for themselves. The real shame comes when these people suffering from depression or a host of other ills stumble into a doctor or therapist’s office with no idea of what has caused their problems. Likewise, there is virtually no support of a psychological nature for family members.

A group of Texas Chaplains is developing a program called Emotional Recovery from Physical Trauma (ERPT).

The ERPT program incorporates:

- A modified defusing technique,5 this is a 3-phase, structured small group discussion provided within hours of a crisis for purposes of assessment, triaging, and acute symptom mitigation. It is a one-on-one crisis intervention/counseling or psychological support throughout the full range of the crisis spectrum.6

- Guided visual imagery techniques is a technique in which mental health professionals help individuals in therapy focus on mental images in order to evoke feelings of relaxation, based on the concept of the mind-body connection.7

- Conversational medicine: For example, when a survivor asks, “where is my son?” after an earthquake, how we respond as chaplains can cause the parent asking the question to have a positive or negative outlook. The chaplain may not know the victim had a child, let alone where the child is located. Perhaps the child was at football practice miles away from the tornado zone. Conversational medicine is choosing words carefully, not making long pauses to traumatic questions (long pauses often equate to negative perception by the survivor) and using rational knowledge of how to get the parent to a safe place first. After the parent has some of their basic needs met, sitting down calmly and logically asking questions to help the parent recall what they were doing before the tornado. “Communication matters in other ways,” Ursula K. Le Guinhas written, “Words are events, they do things, change things…”8

- There are other forms of stress management, such as meditation, yoga, exercise, and practicing breathing techniques.

This program has been established to start the patient on the road to emotional recovery while still in the hospital. It also addresses aftercare and assistance for the family. It is hoped the program will become widely accepted, spread and spawn new ideas to heal the whole patient and the family, in addition to facilitating healthy coping for both patients and their families.

References

- Jeffrey Mitchell, PhD along with others through observation when Dr. Mitchell was a paramedic and firefighter, began to develop a theory about critical incidents and how those incidents could affect individuals if the individuals did not have opportunities to reflect on what exactly happened. Dr. Mitchell with others formed what is now the International Critical Incident Stress Foundation which utilizes a crisis intervention model known as Critical Incident Stress Management, began to have success with tools developed to help mitigate in some the onset of PTSD after experiencing a critical incident. For more information, see https://icisf.org.

- Ibid.

- Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs – see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maslow%27s_hierarchy_of_needs.

- Victim Assistance has become a unique program of providing support to survivors of traumatic experiences. For more information about Victim Assistance and training, go to https://www.trynova.org/.

- Under Jeffery Mitchell, PhD’s crisis intervention model, Defusing is but one of many techniques an individual trained in Critical Incident Stress Debriefing can apply to help mitigate the potential onset of PTSD for a survivor of a traumatic experience – see https://icisf.org and search for “defusing.”

- Ibid.

- “Guided Therapeutic Imagery,” April 27, 2016, see https://www.goodtherapy.org/learn-about-therapy/types/guided-therapeutic-imagery#:~:text=Guided%20therapeutic%20imagery%2C%20a%20technique,concept%20of%20mind%2Dbody%20connection. ;

- Bauer, Sarah C, and Patel, Angira. Meaningful Conversation is a Crucial Part of Medicine. Scientific American, July 28, 2018. See https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/meaningful-conversation-is-a-crucial-part-of-medicine/.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Chaplain LTC (Ret) David J. Fair, PhD, DMin, CTS, FAIS, has served in law enforcement chaplaincy for over 30 years and has been and continues to be an innovative leader in police chaplaincy, crisis intervention and in building relationships. He is President of ChaplainUSA, a nonprofit corporation providing training and education to officers and chaplains. Fair is a veteran law enforcement officer, and a former reserve deputy sheriff.

Fair served with the Texas Military Forces, TXSG-HQ, as a Lieutenant Colonel (LTC), and was chaplain for the 111 EN BN for two years. He served with the Standing Joint Interagency Task Force (STIATF-TX). Fair earned his Military Emergency Management Specialist (MEMS) designation.

Chaplain Fair has served as a briefer on Operational and Combat Stress for the Camp Bowie Training Center. He was deployed on state active duty for numerous hurricanes and served with Operation Lone Star. He is the recipient of the Texas Adjutant General’s Individual Award Ribbon for “Meritorious Conduct” in performance of outstanding service during Hurricane Dolly, response, and recovery. He was certified in Homeland Security at Level V (CHS-V) and carried certification in Disaster Preparedness and Sensitive Security Information. Fair was a presenter for the Board of Certification in Homeland Security, and developed the course, Terrorism Trauma Syndrome. Chaplain Fair served on the Editorial Advisory Board for Inside Homeland Security Magazine where he authored a regular Chaplain’s Column.

Dr. Fair is a member of the Board of Professional Advisors for the National Center for Crisis Management (NC-CM)/ American Academy of Experts in Traumatic Stress (AAETS). He holds their Board Certifications as Expert in Traumatic Stress, School Crisis Response, Crisis Chaplaincy and Forensic Traumatology. Fair is a past member of the Ethics and Professional Policy Committee of the American College of Medical Quality. A longtime emergency medical services technician and volunteer firefighter, Fair served on the City of Brownwood (TX) Emergency Services District Committee, as well as the police and fire committee.

Dr. Fair is an ordained minister and holds a PhD is Pastoral Counseling and Psychology from Bethel Bible College and Seminary as well as a doctorate in Clinical Christian Counseling from Central Christian University. He was on the facility of Wayne E. Oates Institute, a former professor at Bethel Bible College and Seminary, and former member of the Commission on Forensic Education.

For over 20 years, Dr. Fair served as a member of the Brownwood City Council and is a former Municipal Judge and Justice of the Peace. Dr. Fair is Chaplain Emeritus of the Brownwood Police Department having recently retired after 20 years of service. He is also retired from Brownwood Regional Medical Center (now Hendrick Brownwood) as Chaplain following 25 years of service. He was also a volunteer Chaplain for the Texas Department of Public Safety. Fair is past CEO of Crisis Response Chaplain Services and is CEO of the Homeland Crisis Institute.

During police chaplaincy and military service, Dr. Fair was deployed to New York following 911, to east Texas for the Space Shuttle Columbia Disaster, and to Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, Dolly, Gustav, and Ike. Dave has written dozens of articles concerning chaplaincy and trauma as well as authored a book, Mastering Law Enforcement Chaplaincy.

Combat Stress Magazine

Combat Stress magazine is written with our military Service Members, Veterans, first responders, and their families in mind. We want all of our members and guests to find contentment in their lives by learning about stress management and finding what works best for each of them. Stress is unavoidable and comes in many shapes and sizes. It can even be considered a part of who we are. Being in a state of peaceful happiness may seem like a lofty goal but harnessing your stress in a positive way makes it obtainable. Serving in the military or being a police officer, firefighter or paramedic brings unique challenges and some extraordinarily bad days. The American Institute of Stress is dedicated to helping you, our Heroes and their families, cope with and heal your mind and body from the stress associated with your careers and sacrifices.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.