*This is an article from the Spring 2023 issue of Combat Stress

The United States Military Chaplain Corps was created with an Act of Congress on July 29, 1775, by the Continental Congress, who authorized one chaplain for each Regiment in the Continental Army. The title chaplain actually dates to the early centuries of the Christian Church, where they were considered specialists among ministers or priests. Chaplains were set aside for focused ministry or service and typically served in a Chapel attached to an institution or a private home. Today chaplains come from a wide variety of faith traditions and serve our military in ways that relate naturally to the needs of combat Soldiers. Called Chaplain, Father, Rabbi, Imam, Padre, and other approved Armed Forces designations, these women and men provide spiritual and humanitarian care to military and civilian populations as directed by their various commands.

Working with combat Soldiers often places a chaplain in harm’s way alongside those they serve. Though they are not issued weapons and not allowed to engage in combat, they never-the-less have served with courage and distinction across the globe. Recognition has included the highest awards for sacrificial and honorable service in combat and they proudly wear their ribbons alongside those they serve.

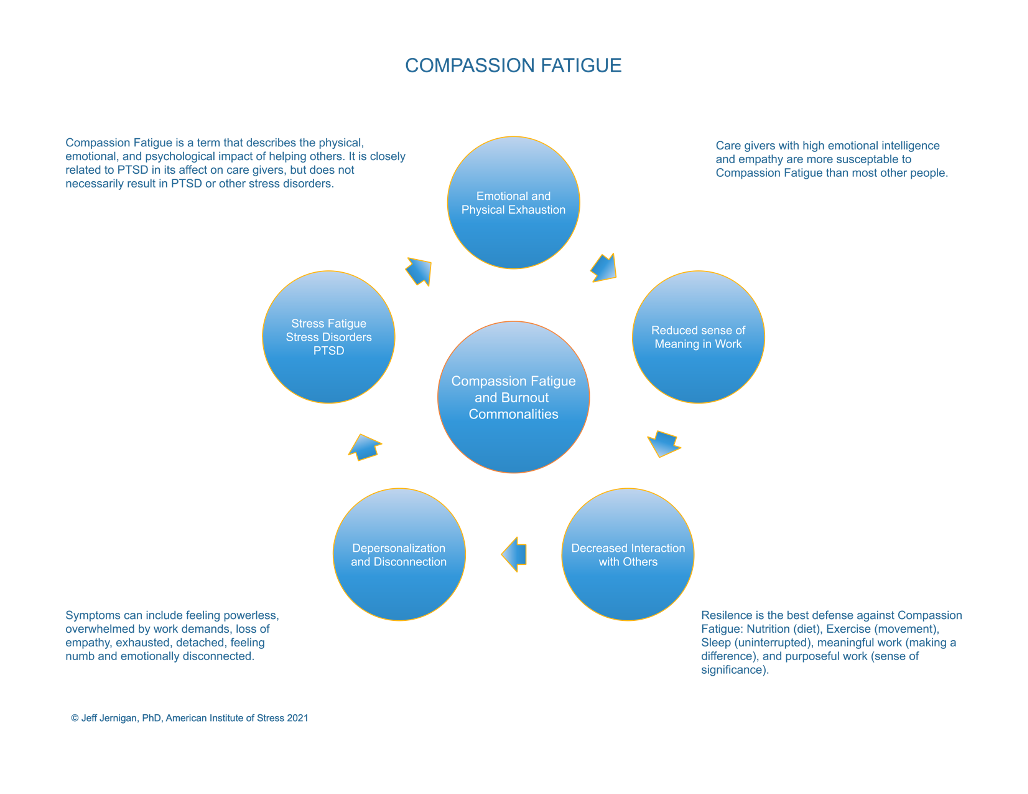

Often acting as first-responders, chaplains are exposed to the same stressors and combat actions that Soldiers are subjected to and under the same hardships and adversity. Serving civilian humanitarian missions, responding to mass disasters and violence, famine and disease, or poverty and hunger, this exposure is true as well. In the midst of leading with compassion in times of risk, crisis, and trauma, they are not immune to stress, fatigue, stress disorders, and post-traumatic stress, including compassion fatigue.1 Compassion Fatigue is a term that describes the physical, emotional, and psychological impact of helping others. It is closely related to PTSD in its effect on caregivers but does not necessarily result in PTSD or other stress disorders.

Caregivers with high emotional intelligence and empathy, such as chaplains, are more susceptible to compassion fatigue than most other people. Stress from sustained fatigue over time can produce physical and emotional exhaustion caused by the depleted ability to cope with one’s everyday environment. Cumulative stress, when unrelieved, can lead to burnout and is characterized by emotional exhaustion, a reduced sense of personal accomplishment, loss of meaning and purpose in work, isolation from others, and depersonalization.2 Compassion fatigue develops slowly over time and often is not recognized until intervention is needed.

Soldier Prays and Meditates

Compassion fatigue produces weariness, brain fog, forgetfulness, frustration, and poor decision- making. When someone refers to having had a tough day by its conclusion, they are usually referring to weariness at the end of a long day. But the reality may be more than tiredness at the end of a long day. Since compassion fatigue can mimic medical burnout. It is always good to ask a follow-up question such as, “How long have you felt this way?” If it is an exception in their experience, this probably does not require addressing. If it represents a pattern it may need to be addressed.

When I was working with one of our medical teams in Eastern Europe some time ago, we were nearly overwhelmed by the demands placed upon us. We were there to address a growing problem of suicide in the military and were also pulled into addressing an epidemic of child suicide in the community. The problem had grown to the point of earning a label: the Blue Whale. The Blue Whale was a social network phenomenon emerging in 2016, which led to suicide among young children and adolescents in astounding numbers. This was fueled, in this instance, by parents leaving the country and their children being left behind to find jobs elsewhere in the European Union in an effort to escape poverty. It is more complicated than that, but one gets the picture.

We worked non-stop with medical and psychological professionals. teaching, modeling Trauma Competent Care (TCC) and helping to care for devastated families.3 Their stories were terrible, their grief profound. We met with social workers, counselors, physicians, and psychiatrists, helping to develop a coherent response to this awful consequence of inadequately- addressed social conditions. Weary, we left the hospital after a long day and I asked a colleague, a psychiatrist in the city where we were teaching, this question, “How are you doing?” He replied with the same statement, “Tough day, I am burned out!” Only, it was more than just a tough day, because I noticed the growing symptoms of weariness, brain fog, forgetfulness, frustration, and poor decision making over the previous ten days. I realized he had been dealing with this for months, I followed up with another question, “What does that mean? How are you really doing?” They were on verge of total physiological and psychological collapse, ready to quit being doctors entirely. Compassion fatigue had led to actual burnout.

Leading with compassion during times of crisis is a hallmark of excellent leadership in any context, but it is especially important for a chaplain.4

When our teams were working post-disaster in Haiti (earthquakes), Sierra Leone (Ebola virus), and Sri Lanka (tsunami), we observed and experienced some unique consequences of compassion fatigue among first responders, including both medical personnel and chaplains. Understandably, our moods were low and our anxiety elevated. But there were also some care givers struggling with mental focus, recall, irritability, and generally muddled thinking. The cause was dehydration.5 The problem with mild dehydration in these settings is that it impairs performance in tasks that require attention, short-term memory skills, and physical movement. It also pushes us further along the spectrum of compassion fatigue as illustrated above.

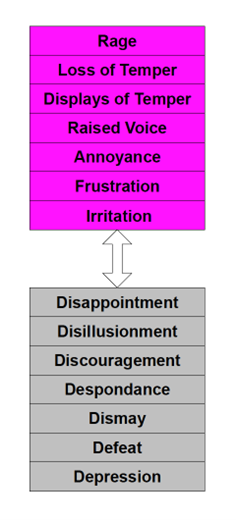

When our frustration reaches a point of behavioral changes, we can find ourselves at odds with others in unimaginable ways. In working with broken families grieving a child suicide, we observed parents reacting differently in their grief and anger. Mothers were overwrought, while many fathers were processing their sorrow differently. Arguments broke out with accusations flying around, directed at how each was responding. Sometimes this has everything to do with gender. Men and women process anger differently, including outward expressions of anger, as well as anger turned inward.6 This can be accentuated between care givers, such as chaplains, who are experiencing vicarious trauma from exposure to the suffering of those they are helping.

The fact that women develop and process anger differently than men reflects a difference in the structure of the brain and is not indicative of one gender or the other being better at processing anger. Men are more often associated with angry responses, but that does not mean women do not ever feel or express anger. In each of the first-responder examples above, the worst arguments erupted between the female and male professionals providing relief and rescue, anticipating that their colleagues would all react the same to the pressure and stress they were enduring.

This may seem to be a minor issue, just like the discussion on hydration. However, the combination of dehydration and misreading cues in the midst of a prolonged crisis situation opens the door to moral distress and moral injury occurring, often without recognition. Moral injury leads quickly to burnout and oftentimes, the end of a career. Chaplains the world over in the international military community that we serve have stories to tell without number.

Moral distress is a psychological phenomenon, quite different from ethical dilemmas or emotional distress.7 Moral distress occurs in a work environment when one knows the right thing to do, but institutional constraints make it nearly impossible to pursue the right course of action. This can occur in any industry where leadership decisions, or indecision, are constrained by institutional requirements or overruled by more senior leaders.8 Over time, moral distress can lead to actual moral injury. A moral injury can occur in response to acting or witnessing behaviors that go against an individual’s values and moral beliefs, eroding self-esteem and confidence, breaking down long and strongly held beliefs about themselves and the world they live in. The result is disillusionment, despair, and eventual physiological and psychological burnout.9 Chaplain’s deal with this consistently in their military organizations, working alongside civilian organizations in the United States, and interfacing with foreign relief agencies structured and led very differently than US military organizations or civilian agencies.

Compassion fatigue is surprisingly easy to guard against or turn around when it happens to you or someone you know. There are five things to practice that will create and sustain resilience. Resilience is key to keeping stress fatigue of any kind at bay. These practices are not new and may sound a lot like what our parents used to tell us as children: eat right, exercise, get enough sleep, keep good company, find work you enjoy doing, and don’t overwork to the extreme if possible. If not possible, take breaks when you can to get away for some needed rest. The difference between then and now is that now we have good science behind this parental advice.

Most of the nutrients our body needs daily in order to function at its best are used by the brain.10 Poor diet, too much junk food, irregular meals, compulsive overwork, and lack of hydration rob the brain of what it needs to function maximally, especially in the face of sustained pressure, demands, and stress. When we exercise sufficiently, an enzyme is produced in our muscles, which travels to the brain and produces a brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). This triggers a process of repair and replacement of neuropathways and brain cells.11 On average, adults need eight hours of sleep.12 During deep sleep, this clean-up function of BDNF takes place. Insufficient sleep and interrupted sleep interfere with this physiological janitorial service. The consequences of poor diet, lack of exercise, and lack of sleep will be foggy mindedness, which negatively affects focus, recall, decision making, self-control, and cognition.

Good friends that you trust and are neither critical nor judgmental are a great source of help in stressful times. Simply being able to talk things out with them, sharing what is going on and what you think about it, as well as how you feel about what’s on your mind is therapeutic.13 Recent studies continue to identify processing as a key intervention with those suffering from stress fatigue and stress disorders, including PTSD. Originally the province of Cognitive Behavioral Theory and a spinoff, Dialectical Behavioral Therapy, processing thoughts and feelings with a trusted active listener now has a label: Cognitive Processing Therapy.14 The point is not to repress or suppress your struggles with compassion fatigue. Consciously or subconsciously stuffing your thoughts and feelings will result in more depression, more anxiety, and more physical illness.

Work can be challenging at times and as chaplains, there often is little control over your work environment in a crisis. This is a great reason to keep your resilience strong through building common sense habits around nutrition, exercise, sleep, relationships, and work you enjoy. The key about work is when it is fulfilling, satisfying, fits your sense of calling and purpose, it can feel like floating down a lazy river in the summertime. Without this kind of resilience, your work will feel like swimming up the rapids all by yourself. Find purpose in your work and let it balance the difficult experiences that challenge your resilience. Also, beware of the undertow!

Compassion fatigue, like most stress-related conditions, is like the undertow in a river or the ocean. It constantly tugs at you in small, barely unnoticeable ways when you are looking for the strong pull of the tide, which never seems to come. So, you get dragged down slowly without noticing the pull. There are three things to take a self-inventory of regularly.15 Poor adaption to life events: everything in life has stress associated with it, including the good experiences, as well as the difficult experiences. Stress is cumulative and can be shed through many of the things we do to relax, including exercise, recreational activities, time with good friends and family, and good health habits as mentioned previously. Self-inventory questions: How am I doing today when it comes to coping with the people and circumstances of the day? Am I up or down? Energized or depleted? Tired but pleased with the day for the most part? How many days in a row have I answered these questions in the negative sense?

If the pattern of too many unsuccessful coping days continues long enough, one will more than likely begin to notice a change in mindset or perspective. You may become more negative than usual, more critical, or judgmental others, wondering where your thick skin has gone because you find yourself easily irritated, frustrated, or outright angry. Here are some additional self-inventory questions: Where did my optimism go? Is my perspective of people and circumstances headed down or up? How many days in a row have I noticed this negative mindset?

As we continue to adapt poorly to life events and this begins to be noticed by others in terms of our perspective and attitude, there is one more opportunity to become more self-aware of a possible spiral downward. Loss of energy and motivation begins to set into the point that those around you may begin to comment, even ask how you are doing. Do not ignore the inquiries. Self-inventory questions: Am I still motivated to do this work, or has my motivation begun to slip? Are my self-care activities the same, improving, or much less? Do I feel ready to quit?

As we continue to adapt poorly to life events and this begins to be noticed by others in terms of our perspective and attitude, there is one more opportunity to become more self-aware of a possible spiral downward. Loss of energy and motivation begins to set into the point that those around you may begin to comment, even ask how you are doing. Do not ignore the inquiries. Self-inventory questions: Am I still motivated to do this work, or has my motivation begun to slip? Are my self-care activities the same, improving, or much less? Do I feel ready to quit?

Poor adaptation to life events, a change in perspective or mindset, and loss of energy and motivation are all signs of movement toward a crisis. Everyone can readily become tired and exhausted at times, but there is little need to remain in this state of fatigue. Get out, take a walk, relax for a moment of conversation with a friend, look up at the blue sky and give your eyes a break (yes, there is good science behind a long view into the distance). Please take care of yourself. What you do is important and there so few who can do it as well as you can. Thank you for more than 247 years of service to our country. Semper Fi.

References

- Jernigan, J., Compassion Fatigue: What to do when caring becomes a burden, keynote presentation: Make-A-Wish Foundation, December 14, 2022

- Jernigan, J., Physical Ramifications of Prolonged Stress: Contentment Magazine, American Institute of Stress, Fall 2020

- Holistic care for infants through adults for trauma and attachment injuries over a lifetime: traumafreeworld.org

- Mazzarelli, A., Winn, C., Leading With Compassion During Times of Crisis: Chief Executive Officer, American College of Healthcare Executives CEO Circle, Fall 2022

- Amen, D., Mild Hydration: Amen Clinics Blog, December 12, 2022

- Amen, D., Surprising Facts About Women’s Anger: Amen Clinics Blog, November 8, 2022

- Jernigan, J., Leadership and Moral Distress: Healthcare Highlights Newsletter, Stanton Chase International, November 2022

- Ritchie, E., Watson, P., et al Editors, Interventions Following Mass Violence and Disasters: Guilford, 2006

- Halpern, J., Nitza, A., et al Editors: Disaster Mental Health Crisis Studies: Lessons Learned from Counseling in Chaos: Routldge, 2019

- Jernigan, J., The Physical Ramifications of Prolonged Stress: Contentment Magazine, American Institute of Stress, Fall 2020

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Pease, J., Martin, C., et al, Impact of residential PTSD treatment on suicide risk in veterans: Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior, Journal of the American Association of Suicidology, Wiley December 2022

- Ibid

- Jernigan, J., Diagnostic and Treatment Complexities of Combat Stress, Combat Stress Magazine; American Institute of Stress, Summer 2022

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jeff Jernigan, PhD, BCPPC, FAIS is a board-certified mental health professional known for influencing change in people and organizations by capitalizing on growth and change through leadership selection and development. Jeff currently serves Stanton Chase Pacific as the regional Life-Science and Healthcare Practice Leader for retained executive search and is the national subject matter expert for psychometric and psychological client support services.

A lifetime focus on humanitarian service is reflected in Jeff’s role as the Chief Executive Officer and co-founder, with his wife Nancy, for the Hidden Value Group, an organization bringing healing, health, and hope to the world in the wake of mass disaster and violence through healthcare, education, and leadership development. They have completed more than 300 projects in 25 countries over the last 27 years. Jeff currently serves as a Subject Matter Expert, Master Teacher, Research Mentor, or Fellow in the following professional organizations: American Association of Suicidology, National Association for Addiction Professionals, The American Institute of Stress, International Association for Continuing Education and Training, American College of Healthcare Executives and the Wellness Council of America.

Combat Stress Magazine

Combat Stress magazine is written with our military Service Members, Veterans, first responders, and their families in mind. We want all of our members and guests to find contentment in their lives by learning about stress management and finding what works best for each of them. Stress is unavoidable and comes in many shapes and sizes. It can even be considered a part of who we are. Being in a state of peaceful happiness may seem like a lofty goal but harnessing your stress in a positive way makes it obtainable. Serving in the military or being a police officer, firefighter or paramedic brings unique challenges and some extraordinarily bad days. The American Institute of Stress is dedicated to helping you, our Heroes and their families, cope with and heal your mind and body from the stress associated with your careers and sacrifices.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.