Diagnostic and Treatment Complexities of Combat Stress

By Jeff Jernigan, PhD, BCPPC, FAIS

*This is an article from the Summer/Fall 2022 issue of Combat Stress

The simple phrase, Combat Stress, suggests there may also be a straightforward remedy.1 Two words, easily understood, have seldom been more complex than these two when put together in the simplicity of one following the other! Hidden beneath the term is a labyrinth of complicated irregular pathways and interactive networks which may lead to successful treatment…. or send the practitioner down yet another rabbit hole. Combat stress is real and can be deadly. Physiological and psychological causes can be difficult to identify at the border of our biology and psychology. It is one of the few moral injuries that can create a lifetime of dysfunction and defy mitigation, simply because it has a viral capability of changing how it affects our psyche and brain chemistry. Combat stress often includes physical, as well as emotional injury and re-injury through lived experiences. Healing, health, and restoration begins in our minds. Yes, exactly – in our minds as both how our mind works and especially, how our brain works as an organ.

There are a number of things to consider when working with people experiencing combat stress, to the point of negatively impacting their ability to function well socially or occupationally.

There is no chronology involved in flashbacks, dreams, or relived life experiences involving combat stress. For many, the memories are as fresh as the moment they occurred. The reaction of a Veteran of the Korean War (1950 to 1953) I was treating was identical to the reaction of a Ukrainian Veteran of the invasion of Crimea by Russia (2014). For both, it was as if the events occurred yesterday. Sometimes a sound, odor, lights, or a specific situation can trigger an episode, whether the trauma occurred 70 years ago, 7 years ago, or recently in the present.

Pre-existing or co-morbid conditions can mask the effects of combat stress and skew our impression of what is going on in someone’s life or otherwise minimize our understanding of a serious condition. It is easy to attribute fatigue, discouragement, and worry to a lack of resilience due to poor diet, lack of exercise, and lack of sleep. In some cases, people experiencing disabling stress may have a history of insomnia due to depression. The question becomes one of are they taking their medication properly? When the answer is no because their prescription(s) ran out, most clinicians are likely to then stop asking questions at that point and to instead, simply respond with a suggestion to get their prescription refilled. We also need to ask more questions in order to eliminate the possibility of a pre-existing or co-morbid condition.

Sometimes a symptom masquerades as a primary diagnosis, hiding the real problem. An active-duty nurse appealed to me for help with a circumstance where she had been insubordinate, publicly and loudly accusing her hospital supervisor of some pretty serious malfeasance. She was facing disciplinary action. She was already being treated for PTSD, including psychotherapy and medication. Things had been going fine until she became increasingly agitated and aggressive at work. When confronted, she exploded into a paranoid rant. Anxiety had not even been on the radar prior to this incident. She was provisionally diagnosed with Paranoid Personality Disorder in connection with their PTSD. Combat stress was assumed to be the underlying cause. When asked to provide a second opinion, taking a thorough history, unlocked a deep secret; not a deep, dark secret from her past, but an inconsequential secret about her present that had enormous implications. She recently had begun an over-the-counter diet program and the diet pills were interacting poorly with the medication she was already taking. This is where the dysfunctional behavior was coming from and not from a personality disorder.

Often times practitioners will provide a provisional diagnosis when there is not enough information to have confidence in a primary diagnosis of someone’s condition. However, as an educated guess, it is assumed further information will be available soon, which will confirm the provisional diagnosis. The problem is that in some cases, no one comes back around with the necessary information that was presumed to be available in the near future and therefore, the provisional diagnosis is never changed. Case in point: a young man remanded to a rehabilitation program was provisionally diagnosed as schizophrenic due to auditory hallucinations, accompanied by aggressive behaviors and severe mood swings. As Clinical Director, the case came to my attention because he was being treated over a fairly long period of time, based upon a provisional diagnosis. When I interviewed the individual, it became clear that the provisional diagnosis had been made in the midst of a detoxification protocol and never followed up. We started the intake process all over again, this time with a truly sober person, discovering that he suffered from severe tinnitus. What he believed were voices in his head were actually the buzzing sounds caused by tinnitus. Sometimes problems are masked under symptoms that make discovery of what underlies, a far greater problem than need be.

All of these distractors, whether you are a healthcare professional or a concerned friend or family member, can be misleading. How to respond effectively and contextually to the one experiencing combat stress suddenly becomes a guessing game. There are three things that can help eliminate the confusion that are common in all of these examples: 1) Take what you see and experience seriously. 2) Get the whole story. For the healthcare professional, this means taking a full history for the record. For the parent, spouse, partner, friend concerned about someone, ask a lot of questions in order to provide a larger context that may give up some clues. 3) Encourage those suffering from stress fatigue, stress disorders, or those in danger of hurting themselves, to get qualified medical help immediately.

Stress is a part of life we have been designed to handle physically and mentally. Too much stress or the wrong kind of stress can have a tremendously negative impact on the psyche and the soma. Because stress is part of life, we tend not to take its impact upon us seriously at times. Sometimes, we do need to take it seriously, especially when it comes to combat-related stress. We will get back to this in a moment. For now, let’s take a look at how stress “messes” with our brains.

Closed Head Injury (CHI) and Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) are sources of physical injury that have medical and psychological consequences. Sometimes these terms are used interchangeably. Here they are used to differentiate the cause of injury to the brain. CHI occurs when the brain is pushed with some degree of violence up against the inside of the skull. The skull is undamaged and remains intact, a solid hard shell within which sits the brain and a very soft tissue organ. An example would be hitting your head on the dashboard because you were not wearing your seatbelt when the driver slammed on the breaks. Your skull impacts the dashboard and remains unbroken, while your brain is thrust up against the inside of your skull, hard enough to cause injury due to the momentum. TBI occurs also when concussive energy passes through the skull and through the brain, with enough force to damage soft tissue. Both can occur at the same time and often do in combat as the result of explosions. Recovery from the potentially disabling effects of CHI and TBI present their own form of stress as the individual struggles to regain lost capacities due to the injury.

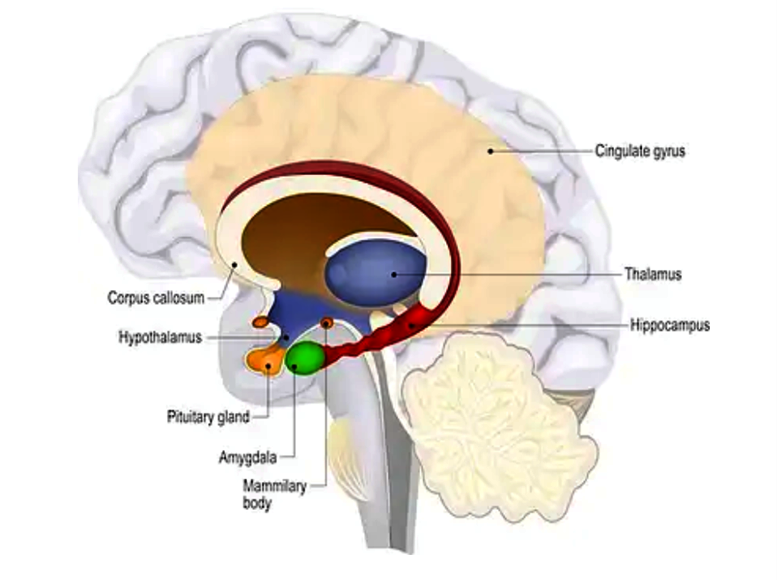

The hippocampus is a very small part of the brain located in the temporal lobe.2 Its job is to regulate learning, memory, memory consolidation, and spatial navigation. It is where short-term memory and learning are turned into long term memories and then stored in the brain. It also helps the process of retrieving memories of personal experiences, as well as facts and information related to those memories. The amygdala, just in front of the hippocampus, is the sentry that looks out for anything potentially threatening and sends out the flight-or-fight signal when danger is recognized.

Aging, stress, neurodegenerative issues involving neural pathways, lack of sleep, obesity, high blood sugar, and especially head injuries, can impair the function of the hippocampus. Under prolonged stress and trauma, the stimulation of amygdala can become so frequent that it becomes oversensitive and can trigger a response that causes reactions in the hippocampus, pituitary gland, and the adrenal glands located on the top of both kidneys. This sets in motion a storm of physical and emotional reactions.3 Our brains are vulnerable to injury from inside the body, as well as from outside the body. Most of the nutrients we need for healthy functioning of our brains are supplied from the food we eat and manufactured in our body. For example, many of the neurotransmitters which facilitate the communication between different structures in our brain are formed from the food we eat in our gut. Exercise and sleep are important to brain health as well. If the hippocampus is damaged due to physical injury or through lack of needed nutrients, a lack of memory, inability to concentrate, inability to learn, panic attacks, depression and anxiety are all part of the constellation of negative effects daily life holds. Negative effects related to combat stress can and do lead to serious negative outcomes. These negative outcomes may show up in PTSD-related suicidal ideation, along with certain environmental factors.

The Army defines combat stress as a common response to the mental and emotional strain that can result from dangerous and traumatic experiences.1 The key word here is “stress.” Stress over a long period of time can also produce PTSD in the absence of trauma. Our concern in this article is stress produced by trauma in a combat environment. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) can develop after a very stressful, frightening or distressing event, or after prolonged traumatic experiences. Our brain gets stuck in the danger mode even after the danger is past. The amygdala, our sentry monitoring threats mentioned previously, becomes overactive and easily triggered causing the parts of our brain handling fear and emotion to get stuck on the “on” mode, so-to-speak.

Suicide remains a major global public health challenge, with more than 700,000 people taking their lives each year.4 Suicide rates for military populations and civilian populations remain relatively the same.5 This makes it difficult to isolate suicide rates for active-duty military personnel and Veterans suffering from combat stress with or without PTSD. However, we do know that there is a link between suicidal ideation, PTSD, and an individual’s perceived burdensomeness and feelings of thwarted belonging. A study focused on Veterans narrows the implications, further identifying baseline loneliness, dispositional gratitude, thoughts of self-harm, and new-onset traumas as the strongest risk factors for suicide attempts.6 These overlapping, yet different conclusions about generally military populations make it difficult to identify specific preventative measures related to the complexities of combat stress. In other words, if you are a Veteran struggling with feelings of burdensomeness and isolation, and have PTSD, you are more likely to consider suicide. Other risk factors include loneliness, fluxing gratitude, and repeat episodes of relived trauma.

Non-Suicidal Self Injury (NSSI) has increased in recent years, adding to the difficulty of identifying NSSI behavior related to traumatic stress, suicidal ideation or rehearsal, or mental wellness issues and conditions.7 NSSI is more common in marginalized populations subject to discrimination. When a member of a military organization is part of a marginalized group, and suffers from PTSD, it is difficult to identify the origin of the self-injury behaviors. Self-injury can include cutting, excessive risk, substance use, and other behaviors that place the individual at risk for injury, but not necessarily suicide. For example, bisexual people are at an elevated risk for NSSI and are among underreported minorities regarding difficulties with self-esteem and thwarted belongingness.8 Sexual orientation does impact reporting of suicidal ideation and NSSI in the general population.9 Though it is practical to understand this affects military minority populations as well, it is very difficult to quantify a subset of those whose experience with combat stress has led to suicide, suicidal ideation, or NSSI. In other words, it may not be possible to determine to what degree self-injury may be associated with combat stress or PTSD.

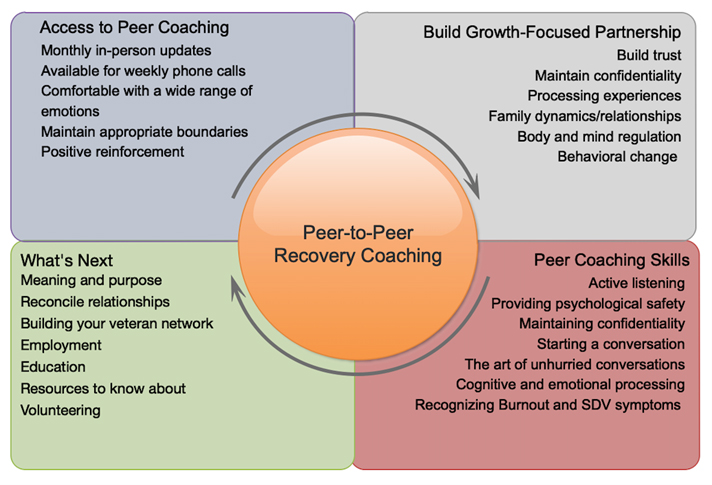

Those experiencing feelings of defeat and entrapment10 due to social isolation and distancing11 are more likely to have a more difficult time dealing with the complexities of combat stress, regardless of any particular stress-related diagnosis or preventative measure. Alongside appropriate medical and mental health treatment, a holistic approach that levels the playing field can be found in peer-to-peer coaching, where relational (versus professional) dialogue and processing over time are crucial to reducing complexity and coming to grips with what the suffering individual is experiencing.12

The term combat stress encompasses a constellation of experiences, conditions, dysfunctions, and diagnoses. Practical evidence-based prevention and treatment strategies exist and are accessible for dealing with the injuries combat stress creates. Long term recovery is served well when Peer-to-Peer Recovery Coaching is used over a twelve month or an even longer period of time.13 Living alongside someone experiencing the effects of combat stress does not have to be a mysterious or confusing adventure. In the infographic above, the arrows indicate the process of peer-to-peer coaching can begin anywhere, depending upon the individual. It can begin with determining what kind of access to peer coaching is most appropriate and convenient for the coach and the Veteran, for example. Next steps include building trust and commitment toward a growth-oriented focus. There are basic coaching skills to be familiar with through practice. The end goal of peer-to-peer coaching is looking to the future thinking, feeling, and acting in ways that create healthy physical and social well-being. Your mind is in order and functioning in your best interest. The coach is a guide to wholeness coming alongside. Look for another article soon that will unpack recovery coaching in detail. In the meantime, seek ways to be of help and encouragement to those wrestling with the often-confusing puzzle combat stress represents.

References

- The United States Army defines combat stress also known as battle fatigue, as a common response to the mental and emotional strain that can result from dangerous and traumatic experiences. It is a natural reaction to the wear and tear of the body and mind after extended and demanding operations: Understanding and Dealing with combat Stress and PTSD, Military One Source, March 2022; https://www.militaryonesource.mil/health-wellness/wounded-warriors/ptsd-and-traumatic-brain-injury/understanding-and-dealing-with-combat-stress-and-ptsd

- com/Blog/Category/Brain-Health/, Brain Structures & Functions: What is the Hippocampus? March 2022

- Jernigan, J., Physical Ramifications of Prolonged Stress; Contentment Magazine, American Institute of Stress, Fall 2020

- Zhen, W., Molassiotis, A., Tryovolas, S., et al, Epidemiological changes, demographic drivers, and global years of life lost from suicide over the period 1990–2019: School of Nursing, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, Department of Social Administration and Social Work; Faculty of Social Sciences, The University of Hong Kong, DOI: 10.1111/sltb.12836, 2021

- Smolenski, D., Parrish, P., et al, Indirect standardization for rare events and a dynamic standard population rate: An analysis and simulation of U.S. military suicide mortalityI rates: Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, Psychological Health Center of Excellence, Defense Health Agency, US Department of Defense, DOI: 10.1111/sltb.12798, June 2021.

- Nichtor, B., Stein, M., Monteith, L., et al, Risk factors for suicide attempts among U.S. military veterans: A 7-year population-based, longitudinal cohort study: Suicide and Life Threatening Behavior, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and the National Institute on Aging, 2021

- Cathelyn, F., Van Dessel, P., De Houwer, J., Predicting nonsuicidal self-injury using a variant of the implicit association test: Department of Experimental-Clinical and Health Psychology, Ghent University, DOI: 10.1111/sltb.12808, 2021

- Dunlop, B., Coleman, S., Hartley, S., Carter, L., et al: Self-injury in young bisexual people: A microlongitudinal investigation (SIBL) of thwarted belongingness and self-esteem on non-suicidal self-injury: 1Division of Psychology and Mental Health, School of Health Sciences, The University of Manchester, DOI: 10.1111/sltb.12823, 2021

- Stinchcomb, A,. Hammond, N., Sexual orientation as a social determinant of suicidal ideation: A study of the adult life span, Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, DOI: 10.1111/sltb.12754, 2021

- Moscardini, E., Okey, F., Robinson, A., et al, Entrapment and suicidal ideation: The protective roles of presence of life meaning and reasons for living: Department of Psychology, Louisiana State University, School of Psychological Sciences and Health, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, UK, Department of Public Health Sciences, University of North Carolina at Charlotte, DOI: 10.1111/sltb.12767, 2021

- Holer, I., Rath, D., Teismann, T., et al, Defeat, entrapment, and suicidal ideation: Twelve-month trajectories: Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, DOI: 10.1111/sltb.12777, 2021

- France, D., Springer, S., Jernigan, J., et al: Applications of the Public Health Approach to Suicide Prevention for Military Afflicted Population; France, Springer, Jernigan J, Jernigan N, Jachminic; contributing authors and editors, American Association of Suicidology, 2021

- Ibid

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jeff Jernigan, PhD, BCPPC, FAIS is a board-certified mental health professional known for influencing change in people and organizations by capitalizing on growth and change through leadership selection and development. Jeff currently serves Stanton Chase Pacific as the regional Life-Science and Healthcare Practice Leader for retained executive search and is the national subject matter expert for psychometric and psychological client support services.

A lifetime focus on humanitarian service is reflected in Jeff’s role as the Chief Executive Officer and co-founder, with his wife Nancy, for the Hidden Value Group, an organization bringing healing, health, and hope to the world in the wake of mass disaster and violence through healthcare, education, and leadership development. They have completed more than 300 projects in 25 countries over the last 27 years. Jeff currently serves as a Subject Matter Expert, Master Teacher, Research Mentor, or Fellow in the following professional organizations: American Association of Suicidology, National Association for Addiction Professionals, The American Institute of Stress, International Association for Continuing Education and Training, American College of Healthcare Executives and the Wellness Council of America.

Combat Stress Magazine

Combat Stress magazine is written with our military Service Members, Veterans, first responders, and their families in mind. We want all of our members and guests to find contentment in their lives by learning about stress management and finding what works best for each of them. Stress is unavoidable and comes in many shapes and sizes. It can even be considered a part of who we are. Being in a state of peaceful happiness may seem like a lofty goal but harnessing your stress in a positive way makes it obtainable. Serving in the military or being a police officer, firefighter or paramedic brings unique challenges and some extraordinarily bad days. The American Institute of Stress is dedicated to helping you, our Heroes and their families, cope with and heal your mind and body from the stress associated with your careers and sacrifices.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.