Dreams, Nightmares, and Disturbed Sleep

*This is an article from the Summer 2021 issue of Combat Stress

By Jeff Jernigan, PhD, BCPPC, FAIS

Our family tree is inhabited by five generations of combat Veterans, going back to WWI with 153 years of cumulative service acknowledged with 73 combat-related decorations, in addition to the usual collection of campaign ribbons, shooting badges, wings, parachutes, and dolphins. We talk a lot about dreams and nightmares…a lot. Among siblings and cousins, aunts and uncles, parents and children: it has been an ongoing cross-generational conversation for as long as I can remember. All of it is difficult because it is not the usual bantering and exaggerated storytelling brothers and sisters-in-arms are known for throughout history. This is the stuff of wet eyes, deep grief, lingering guilt, haunting shame, and very few answers. We have learned some answers lay in the community formed by our pain and being listened to, understood, and taken seriously by those who KNOW. This is where acceptance can be found when we are not accepting of ourselves and we want the dreams and the nightmares to stop.

Dreams are a natural product of our physiology and psychology and play a healthy role in our lives.[1] Dreams can be responses to our external environment. For example, a noise heard in the night that doesn’t fully wake us up but requires a rational explanation. Dreams can also be a response to our internal environment: too much pepper on too much pizza we had for dinner that is now talking back to us with discomfort. Again, it is a physical stimulus our mind requires an explanation for and uses imagination and creativity to produce an answer. Our mind always seeks congruity.[2] It likes balance, calm, and tranquility like a pool of undisturbed water, reflecting mirror-like the peace and balance it needs.

Dreams are also a mechanism for working out solutions while we sleep. How many times have you awakened in the night with an idea, a solution, an answer and turned over and gone back to sleep, telling yourself you will remember it in the morning…only you don’t! That’s one reason I keep a notepad on the night table beside the bed. Stress is usually the culprit when this happens. But stress can get out of hand. It depends on what your unconscious mind is trying to work out.

Often, our unconscious mind shifts into problem solving mode while we sleep but is missing a few pieces of the puzzle. When we sleep, problem solving can be more difficult than when we are awake because working memory (where thinking goes on) must access short-term memory and long-term memory, as well as other structures in our brain that may be off-line. When there is a mix-up, our mind will borrow a bit of recollection from something else and slip it into the empty spot it is trying to fill.[3] This can create some very interesting associations in our dreams! This hiccup in trying to rationalize our thoughts while sleeping happens because our brains work differently in some respects while we are asleep.

While we sleep and dream, our brain is working without the benefit of our logic filter.[4] This can make for some spectacular dreams! Recently I had a dream where I was piloting a jet fighter. Ready for take-off at the end of the runway, I was cleared for departure. It was a very vivid realistic dream! I could hear the engines spool-up, feel the uneven thumping of the landing gear as the aircraft began to gain speed down the runway, and saw the nose lifting as I pulled back on the stick and the runway fell away below. And then I crashed. My wife was awakened by my hand and leg motions, and when I leapt out of the bed, diving up into the air only to crash to the floor, hitting my head on the side table, she panicked. To make matters worse, I was awake now, leaning back against the bed, laughing aloud as I realized what happened. She thought I had lost my mind. Dreams can be very realistic and very persuasive to the dreamer. This will be important when we get to nightmares.

The brain is a magnificent organ.[5] When we dream, the Temporal Lobe and Limbic System are involved. The Temporal Lobe is where much of our ability to remember, imagine, and dream resides. It has a large number of substructures dedicated to other things as well. Related to dreaming, some of these structures involve perception, facial recognition, understanding language, and emotional reactions. The Limbic System fires up during dreaming as well. This is where processing and regulating emotions goes on. Our response to stress is centered here, as well as self-regulation and pursuit of pleasure and avoidance of pain.

The Amygdala and Hippocampus are located in the Limbic System and play an important part in dreams, especially nightmares.[6] The Amygdala acts like a sentry and sounds the alarm when it senses danger. It doesn’t know the difference between being awake or asleep and sounds off in response to any perceived threat. Among other things, fear-learning starts here and triggers responses in areas of the cortex that process cognitive functions as well as brainstem systems that control physiological responses; like taking off in a jet fighter, for example. This is where our flight or fight response comes from. The Hippocampus is the structure in the brain most closely aligned with memory formation. It turns long-term memory into permanent memory, which plays a role in nightmares related to trauma and which can endure much longer than an ordinary dream. It is also involved in spatial navigation, which is why we can do so many seemingly miraculous things in our dreams, like fly unaided through the air, create fire with the snap of our fingers, or disappear in one room and appear in another. Logical thinking and reasoning are located in the Frontal Lobe and not directly involved in dreaming, so dreams become a place of marvelous adventures, and also can become a place of unnatural terror.

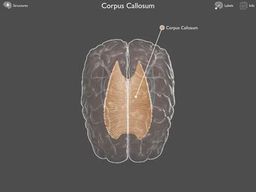

All these structures in the brain are tied together by the Corpus Collosum which acts as the wiring connecting all the parts. We call this white matter, while the structures in the brain connected in this manner are referred to as grey matter. There are any number of things that can affect the white and grey matter in our brain, including diet, exercise, and sleep. Neurotransmitters in our brain, for example, facilitate this communication along neural pathways. These neurotransmitters are created in our body from the food we eat. Exercise is important for many reasons with one of special importance to the brain. While we exercise intensely, an enzyme is produce in our muscles, which travels to the brain, where it stimulates the production of a Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF) which, in turn, acts to clean up our brain while we sleep. Bad diet, lack of exercise, and sleep disturbances can trigger dreaming.

Dreaming has a signature that can point to what you are dreaming about.[7] The “pointing” is to something our mind is trying to resolve. It could involve confronting the emotional dramas in our lives. It could be working out solutions to practical problems involving real world challenges. School or work-related challenges like understanding fractions or conquering the new software just rolled out at work. It could be simply trying to remember something that was handed off to our unconscious mind by our conscious mind as we fell asleep, or in other words, what we were thinking about just before we fell asleep. Or, it could be the struggle with feelings of betrayal, especially when it involves deeply held values. It could be repeated attempts of our mind to reconcile deeply held beliefs about ourselves, others, or the world we live in to the trauma we have been subjected to by that very same world. This is the stuff of nightmares.

Nightmares are disturbing feelings of anxiety, fear, perceived guilt or shame, and danger.[8] Post-traumatic nightmares involve the region of the brain involved in fear behaviors, including the Amygdala which perceives the potential for harm, and sounds the alarm, lighting up the brain, just as it would if an angry bear were chasing us through the woods in real time. Fight or flight kicks in; fear, anxiety, and panic take over.[9] If this occurs regularly enough over a long period of time, the Amygdala becomes sensitive, especially to over-exposure to trauma. Bad dreams and nightmares can become so regular by this point, that one can actually be afraid to go to sleep. This is where the Hippocampus gets involved through moving recalled traumatic experiences, like combat, into permanent memory.[10] Common triggers for nightmares are stress, anxiety, irregular sleep, medications, mental health disorders, and especially PTSD. So, what can we do about nightmares?

Diet, exercise, and sleep have already been mentioned. So has processing, though obliquely in the beginning of this article. Processing refers to the conversations with others you know accept you without criticism and are not judgmental. You can trust them with anything you share, knowing they will keep your confidence. They will actively listen and engage you in conversation with empathy. This is the kind of sharing my family has done for generations regarding our traumatic experiences. It brings deep issues to the surface, where they can be understood more clearly. It provides a framework for rebuilding self-image and world view. It provides a verbal blackboard for asking questions, sharing answers, and exploring options. What remains under the table cannot ever be fully known, resolved, or healed. Processing is a benevolent yet sometimes difficult way to get things on top of the table, seen for what they are with the promise and hope of healing through being listened to, understood, and taken seriously.

This experience became the impetus for research into recovery coaching for Veterans and a four-year pilot program recently recognized as peer-to-peer coaching approved for use with military personnel, Veterans, and their families.[11]

There are other things to consider as well. Check the side effects of any medications being taken. Avoid reading, watching, or listening to any media that has content you know or may suspect triggers your nightmares. If a dream awakens you, don’t lie in bed trying to go back to sleep. Get up, walk around a bit, drink some water and then return to bed. This will help kick in your logic filter and reset things. Look for any changes in behavior that are unusual and represent a change. A pattern of unusual sleep disturbance and behavior is an early warning sign for stress fatigue which, if unchecked, can trigger bad dreams and nightmares. Be proactive and seek help from a qualified healthcare professional if nightmares persist.

Understanding the biology of dreaming demystifies them and lessens their power over us. There are practical things we can do to maintain a robust physiology, beginning with diet, exercise, rest, and staying engaged in community. Taking care of our body also takes care of our mind. However, it is a two-way street, and our psychology can impact our physical health as well. Understanding the psychology of dreaming takes it out of the realm of hocus-pocus and frees us from the burden of suspecting something is broken beyond repair. This is where peer-to-peer processing can help free us from a cycle of bad dreams and nightmares.

Trauma comes in many forms. It can be the result of moral injury (a response to acting or witnessing behaviors that go against an individual’s values and moral beliefs) or the result of major traumatic events. Sustained stress and uncertainty over a long period of time can produce the same results. Even witnessing how other people, especially significant others, respond to trauma in their lives can produce vicarious trauma in us. Depression and anxiety often accompany trauma as we attempt to move past the experience. Self-medication, avoidance and isolation from others, and pursuing pleasure as a means of escape complicate things further. This is a cycle that can be broken, but not without help from others.

Dreams are our friends. They help us figure things out, resolve issues, find solutions, and explain the unexplainable. They even can be recreational. When they are no longer friendly or helpful, it is time to figure out why. What are they pointing to that you can do something about? May all your dreams be the stuff of warm days, good times, and cool breezes.

- Jernigan, J, The Well Being and Mental Health Spectrum, Instructors Guide: Sana Inititiative, Ministry of Health, Rwanda, 2019

- Kaufman D, Meyer H, Milstein, M, Clinical Neurology for Psychiatrists, Sleep Disorders, Eighth Edition: Elsevier 2013

- Lynn, S, McConkey K, Editors, Truth in Memory, Expectancy Effects in Reconstructive Memory: Guilford Press 1998

- Dreup, M, How Dreams are Related to Your Health: Cleveland Clinic, May 2017

- 3-D Brain Images and Explanations, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, 2015

- Ibid

- Davis, N, The Dreaming Brain Has a Signature: Journal of Nature Neuroscience, March 2017

- Sing, A, Sini, E, What are Nightmares: Sleep Foundation, October 2020

- On the Brain, Lecture: Harvard Mahoney Neuroscience Institute, Harvard Medical School Autumn 2015

- Wanesley, How the Brain Controls Dreams: Department of Psychology and Program of Neurology, Furman University Press, June 2020

- Jernigan J, Jernigan, N: Peer-to Peer Recovery Coaching: Restoring and Improving Veteran Connections; AAS National Task Force on Improving Veteran Access to Mental Health Resources, France D, et al Editors; Applications of the Public Health Approach to Suicide Prevention for Military Afflicted Population, American Association of Suicidology, 2021

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jeff Jernigan, PhD, BCPPC, FAIS is a board-certified mental health professional known for influencing change in people and organizations by capitalizing on growth and change through leadership selection and development. Jeff currently serves Stanton Chase Pacific as the regional Life-Science and Healthcare Practice Leader for retained executive search and is the national subject matter expert for psychometric and psychological client support services.

A lifetime focus on humanitarian service is reflected in Jeff’s role as the Chief Executive Officer and co-founder, with his wife Nancy, for the Hidden Value Group, an organization bringing healing, health, and hope to the world in the wake of mass disaster and violence through healthcare, education, and leadership development. They have completed more than 300 projects in 25 countries over the last 27 years. Jeff currently serves as a Subject Matter Expert, Master Teacher, Research Mentor, or Fellow in the following professional organizations: American Association of Suicidology, National Association for Addiction Professionals, The American Institute of Stress, International Association for Continuing Education and Training, American College of Healthcare Executives and the Wellness Council of America.

Combat Stress Magazine

Combat Stress magazine is written with our military Service Members, Veterans, first responders, and their families in mind. We want all of our members and guests to find contentment in their lives by learning about stress management and finding what works best for each of them. Stress is unavoidable and comes in many shapes and sizes. It can even be considered a part of who we are. Being in a state of peaceful happiness may seem like a lofty goal but harnessing your stress in a positive way makes it obtainable. Serving in the military or being a police officer, firefighter or paramedic brings unique challenges and some extraordinarily bad days. The American Institute of Stress is dedicated to helping you, our Heroes and their families, cope with and heal your mind and body from the stress associated with your careers and sacrifices.