Physical Ramifications of Prolonged Stress

By Jeff Jernigan, Ph.D., BCPPC, FAIS

*This is an article from the Fall 2020 issue of Contentment Magazine.

I pulled into the client’s corporate headquarters a little early to check things out. Two parking spaces over there were two people getting lunch bags out of the trunk of one of their cars and arguing loudly about whether or not they had enough for everyone. As it turns out, they were one lunch short. It turned out to be mine. When they discovered they missed one, they were mortified. But that came later in the midst of emotional chaos.

The organization had just called their leadership team back together a week ago to plan the reengagement of their workforce. Immediately things went downhill fast and division bordering on warfare had broken out between two factions: a small group who had remained at work as essential personnel during the preceding three-plus months, and the group that worked remotely during this time.

Some of those who remained at work suspected the remote workers were coasting, taking advantage of the time away for a holiday, and weren’t working very hard. This suspicion evidently had taken root when a few of the remote workers were asked to come back temporarily to provide some help and were not able to do so. When the remote group did come back to work, they were surprised to experience how much the relationships among those who saw each other every day in the workplace had moved forward. Conversations about work, family, and others in the organizational network across the country sounded like a foreign language to the remote workers. They felt left behind and shunned.

Hurt feelings, angry suspicions, and distrust stoked the flames of the withdrawal, fear, anxiety, worry, and distress everyone felt. Will we keep our jobs? What do I do about the kids when I go back to work, and the schools aren’t open yet or close again? What will the company do to fix this mess? What have they done to protect us at work that is different from before? Will there be layoffs? Cooped up for months, it feels like we are coming back to work with more stress than I have at home! And, this is actually true.

A Readiness to Return to Work assessment being developed by MindShift reveals that most people returning to work experience more stress and not less.1

This is a result of some stressors remaining unchanged, like what to do with children or others in the home needing care. Other stressors are adaptations of preexisting worries: what about my raise; will I be laid-off because of the downturn in business; I am underwater on the rent for my apartment, how am I going to pay my bills? Some stressors are new: what happens if my workplace turns into a new hotspot; I feel sick all the time, headaches, stomach aches, and now I have a rash all over my back that burns when I get worked up. I am getting sicker by the day, cannot sleep, angry all the time, crying for no reason in all the wrong places. And now, I have forgotten the lunch for the guy we brought in to bring peace and confidence under our roof once again. To make it worse, he did not say a word, and no one figured it out until lunch was over. We are all schmucks!

The Relationship Between Stress and Illness

Stress is cumulative. Good stress and bad stress all add up, and our body doesn’t know the difference. If stress is not managed and shed appropriately, it starts to take over our lives. Our minds are designed to work with this reality and when it is overloaded, it will shift stress into physical maladies to lessen the strain on mind and body. Only, it actually is simply displacing the stress into our bodies instead of removing it from our lives. This process is called somatization: the production of recurrent and multiple medical symptoms with no discernible organic cause.2 More simply put, conversion of a mental state (such as depression or anxiety) into physical symptoms.

There is a long list of things that can go downhill quickly as a result of stress in addition to the symptoms the individuals above were experiencing. Some of these are quite serious: fibromyalgia, diabetes, strokes, cardiac disorders, compromised immune system, little resistance to colds, personality disorders, stress disorders, and more. The very first sign of a stress disorder is sleep disturbance and changes in behavior which were previously not observed or experienced.3 This is the beginning of a pattern which can result in stress fatigue, burnout, and suicidal ideation if not interrupted and resolved.

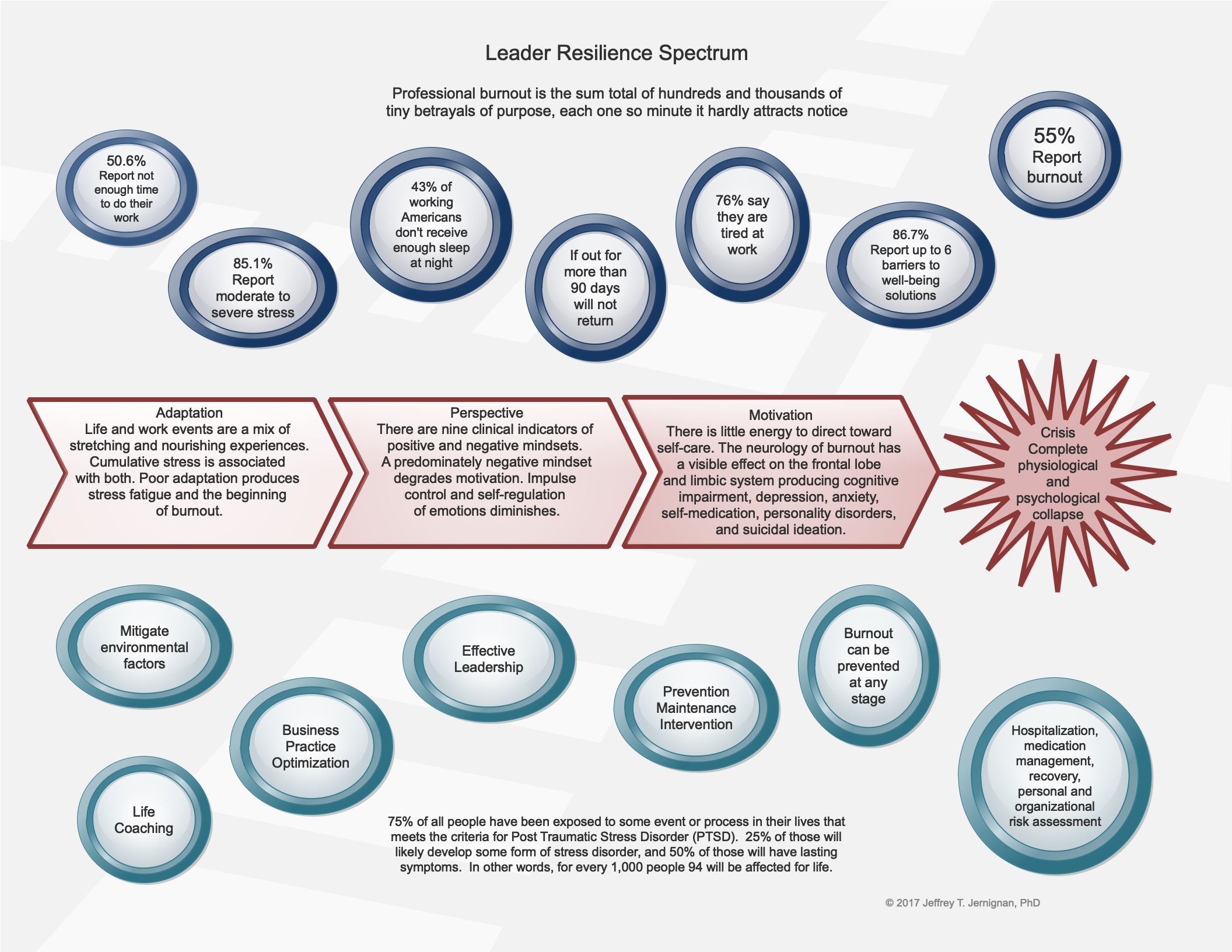

Our physiology impacts our psychology. The leadership team in the opening story has been under prolonged stress which can also include trauma. This impacts their relationships, their disposition and personality, their ability to reason, ability to focus, memory, and their physical health. This pattern is illustrated in four stages:4

Everything in life stretches us, and stretching experiences have stress associated with them. This may be wonderful, enjoyable experiences involving family, friends, work, or simply a great time alone doing something you enjoy. Or, it could be difficult or even unpleasant experiences. This is called Life Event Stress. For the most part, our minds and bodies can manage this stress very well. Good stress, also called Eustress, and unhealthy stress is cumulative and can overwhelm our abilities to manage or shed our stress well. The measure of our resilience, the duration of this cumulative stress, and any trauma that may be involved determine our ability at any time to adapt well to life events. When poor adaptation results in unrelenting stress fatigue, we begin our journey across the spectrum of stress disorders, burnout, and crisis. This journey can be interrupted and turned around at any moment.

If this is not turned around, our affect and mood can begin to change. Our mindset, or perspective becomes increasingly negative, pessimistic, and cynical. Our behavior changes and cognitive functions begin to become affected. A sense of hopelessness begins to set in. Serious physical and emotional symptoms begin to appear. Eventually, our motivation is sapped, and we have little energy, even for self-care. At this point, escape and release become drivers and suicidal ideation is a risk.

Understanding How Stress Impacts Neurology

Just as our mind affects our body in creating illness through somatization, our body can affect our mind and how it functions as an organ. A poor diet consisting of largely junk food can create hypoglycemia, a condition resembling depression. Consuming too many meats containing antibiotics can interrupt the production of neurotransmitters, impacting how various structures in our brain communicate with one another. Lack of sleep and sleep disturbance can interfere with the brain’s ability to repair and replace brain cells and neural pathways. Lack of exercise can cause a buildup of various unhealthy toxins. All of this can cause problems with thinking, reasoning, decision making, memory, and self-control.

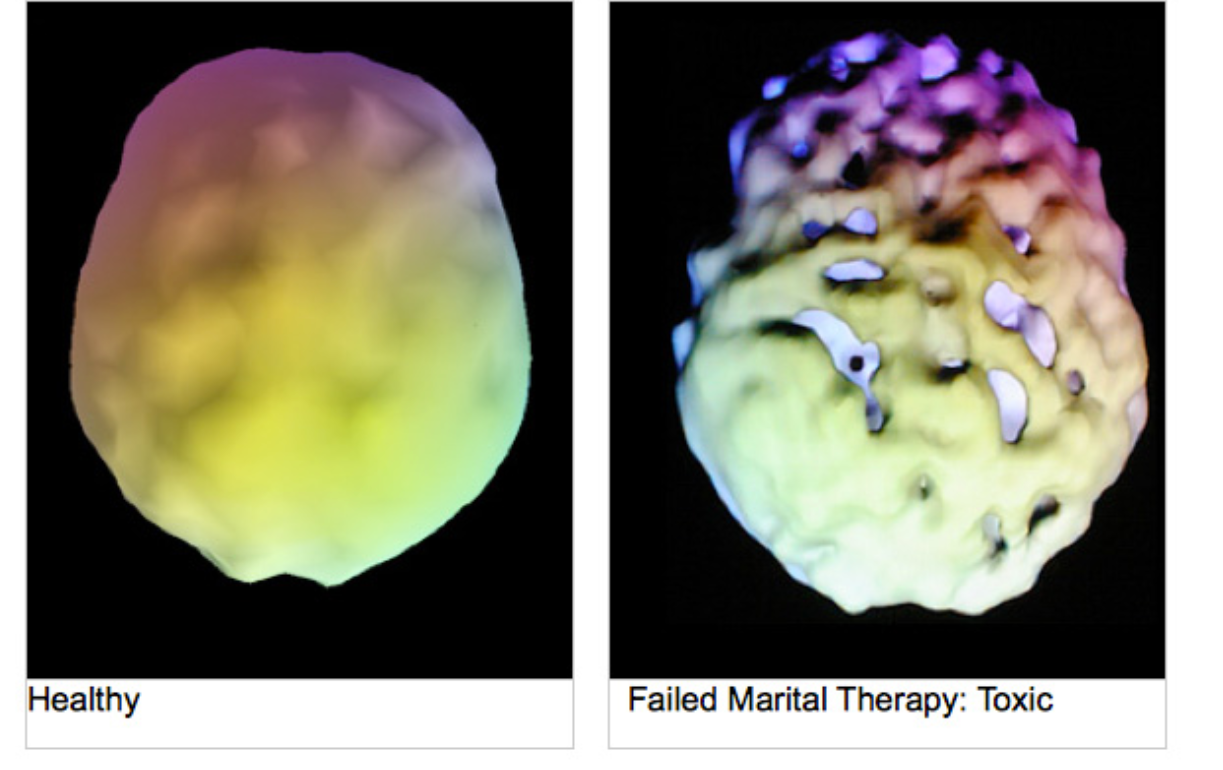

Add stress to this and you can create the appearance of personality disorders, paranoia and phobias, withdrawal and schizoid behavior, depression, anxiety and panic attacks. At some point, your brain starts to shut down. Metabolism in various parts of your brain lowers. Then what appears to others as mental illness may begin to surface. Here are two scans of brain activity, one of a healthy normal functioning brain, and one of a stressed-out spouse struggling in their marriage in a toxic relationship.5

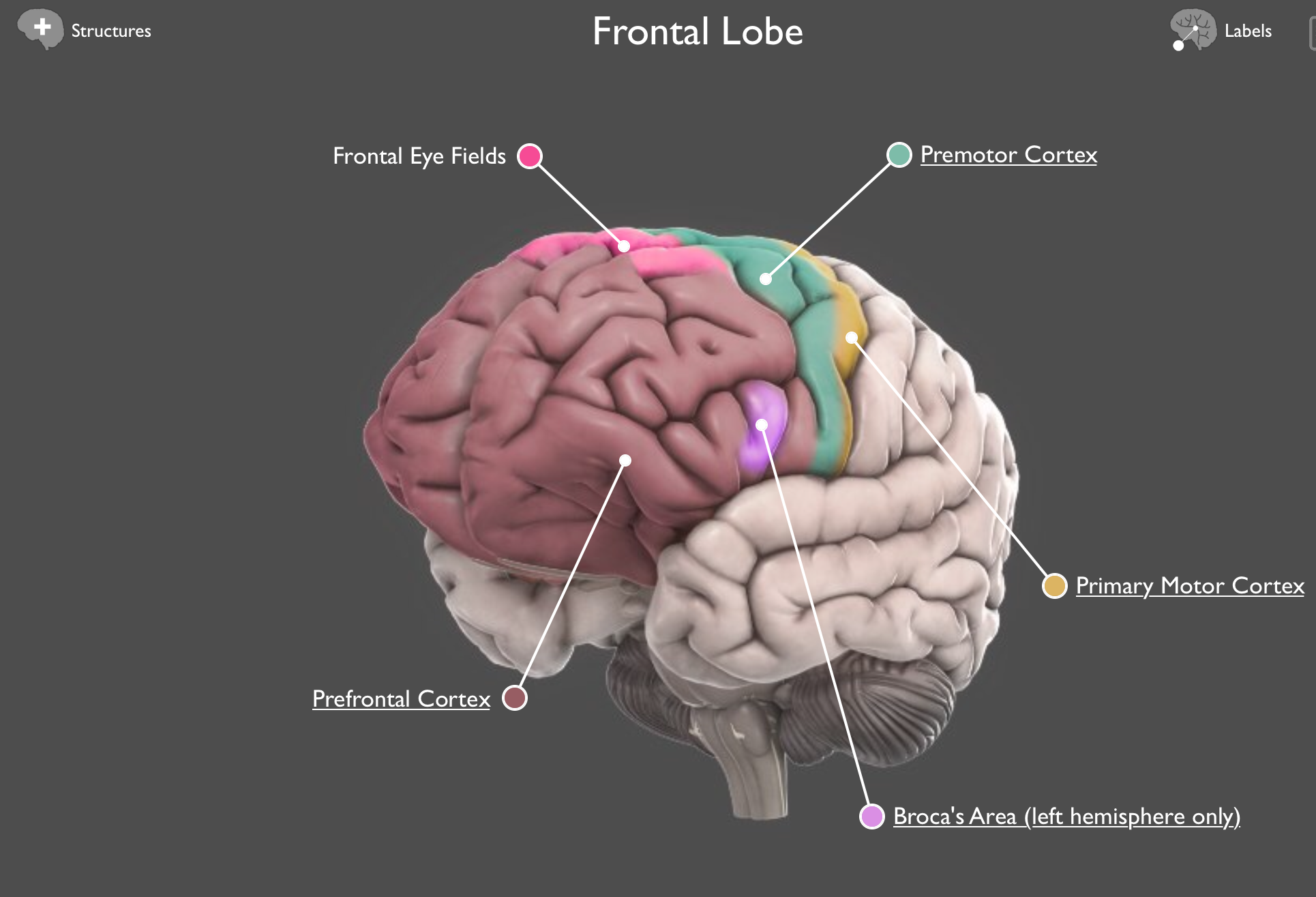

The top view scan on the right appears to show holes appearing in the brain. There is actually brain matter here, but the brain scan reveals areas of very low metabolism as if there was nothing there. These areas of the brain are very low functioning, affecting thinking, emotions, and behavior. Here is an illustration of our brain and the function of various structures.6

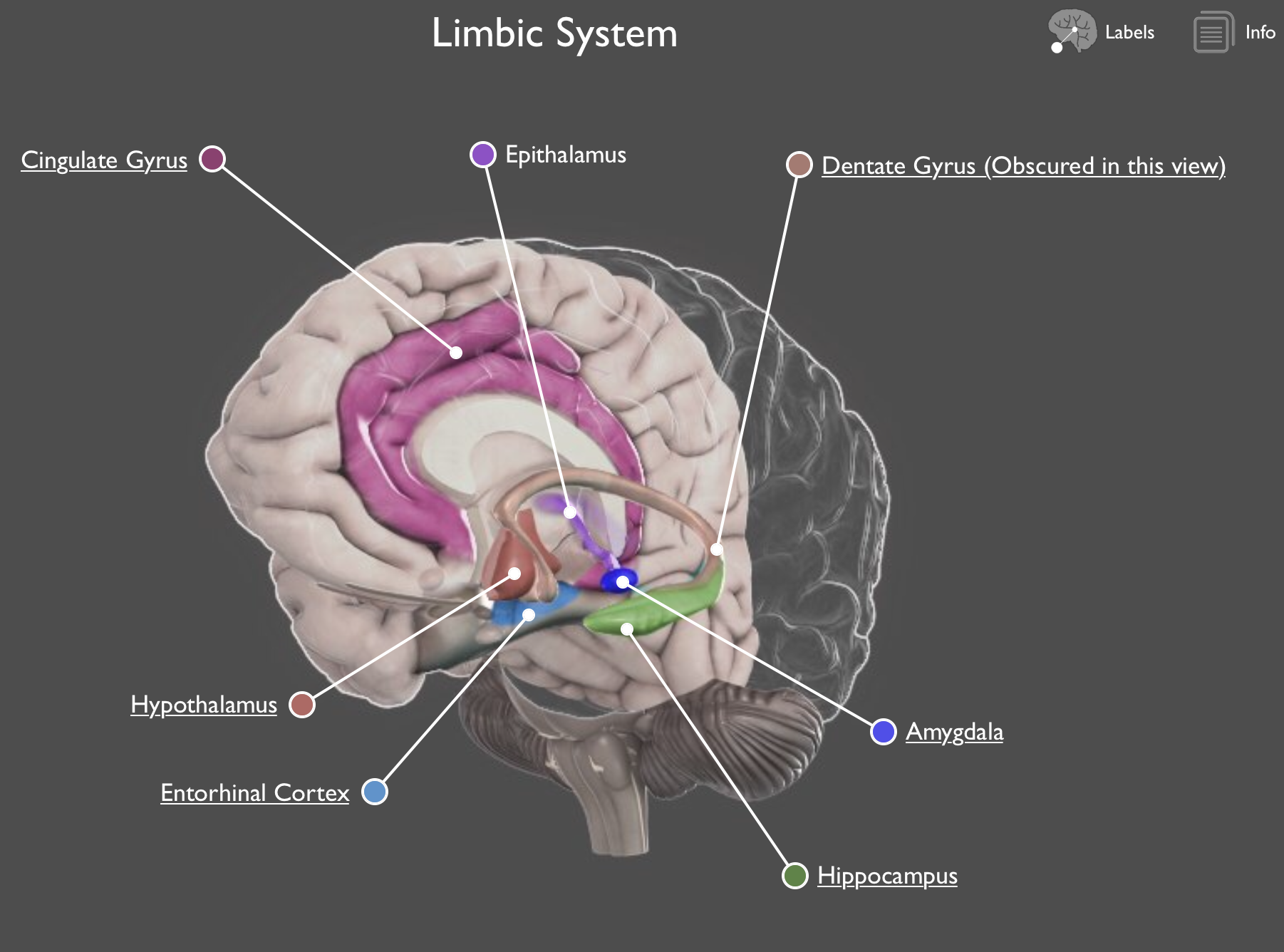

The Limbic System is the emotional center: self-regulation and control. The amygdala is the center for anger, fear, danger awareness, fight or flight response. The hippocampus plays a key role in encoding new memories used in rational thought as well as recall. The hypothalamus is the master control center for the endocrine system (over 60 hormones). The ventral striatal is involved in motivation. The cortex gives us conscious thought and reason. The prefrontal cortex is where planning ahead, considering consequences, and managing emotional impulses is centered.

The Frontal Lobe is where the executive functions are located: working memory (what we think with), planning, calculating, strategy, reasoning, logic, abstract thinking. All of these structures are impacted by stress as well as how we treat our body when it comes to nutrition, sleep, exercise, and meaningful relationships.

Managing the Ramifications of Prolonged Stress

Our first line of defense is to take care of our body and our mind so they can take care of us. We know now that the body affects the mind and the mind affects the body. We have to be mindful of both our physiological health and our psychological health at the same time. Nutrition, exercise, sleep, and meaningful relationships are foundational. This is where resilience is created, built, and sustained.

Building on that foundation involves healthy processing. Processing involves bringing out from what is under the table (denial) and putting it on top of the table where we can deal with it effectively (authenticity). Processing stress is key to shedding stress. Shedding stress is key to managing stress in our lives.

This may involve journaling your experiences; sharing your experiences with trusted friends who can identify, empathize and interact with you with non-judgmental understanding; balancing stretching experiences with nourishing experiences; and creating appropriate life and work boundaries in your routines. In other words, meaningful relationships help you process stress. Self-reflection, interaction with safe others, giving yourself a recess before boundaries are crossed for too long a period of time, reflecting on your own stories while helping others reflect upon their own are part of Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT). DBT tries to identify and change negative thinking patterns and advocates for positive changes. It may be used to treat suicidal and other  self-destructive behaviors. It is not counseling or coaching per se, but a method for de-escalating through mindfulness, interpersonal effectiveness, building tolerance to distress, and building better emotional regulation.

self-destructive behaviors. It is not counseling or coaching per se, but a method for de-escalating through mindfulness, interpersonal effectiveness, building tolerance to distress, and building better emotional regulation.

You don’t have to see a therapist to benefit from these concepts. Interaction with others whom you can trust enough to be who you really are, knowing they will remain non-judgmental, accept without criticism and be appropriately transparent and vulnerable with their own experience is a place to start. Some may need more guidance from a coach or counselor. Some may need even more help. If you choose not to apply anything you have discovered in this article, it is only a matter of time before you will be in serious physical and emotional trouble. The nice thing about sleep is you can gain back what you lost. Stress is different. Stress injury can go on for years and not result in a complete physiological or psychological breakdown. But it will prolong recovery. One year of prolonged stress can require as much as three years for complete recovery including establishing new boundaries, new habits, and new thinking well beyond what physical and emotional recovery requires.

We can hold up well under prolonged stress easily through understanding the nature of stress and applying these simple straightforward ideas built around nutrition, exercise, sleep, and meaningful relationships. What is hard is breaking old habits, building new ones, and creating healthy boundaries that steer you toward healthy relationships. Fear and worry are not our friends in this process and can erode progress we make toward managing our stress. Remember, we can’t solve our problems with the same thinking that created them.7 Our worries do not empty tomorrow of its sorrows. It only empties today of its strength.8 Let’s embrace changes that free us from the ramifications of prolonged stress.

References

- Preparing for the Mental Health Needs of Returning Employees, Rex Miller; MindShift 2020

- Miriam Webster Unabridged Dictionary; https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/somatization, June 30, 2020

- Self-Directed Violence Prevention, Jernigan, PhD; Olive Branch International, Moldova Ministry of Health, Moldova Ministry of Defense National University; 2017, 2018, 2019

- Stress Disorder Patterns, Jernigan, PhD; The Barnabas Group, October 2019

- The Neurology of Burnout, Jernigan, PhD; HVG, May 2017

- Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, 2016

- Einstein

- Corrie Ten Boom

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jeff Jernigan, Ph.D., BCPPC, FAIS is a board-certified mental health professional known for influencing change in people and organizations by capitalizing on the growth and change through leadership selection and development. Jeff currently serves Stanton Chase Pacific as the regional Life-Science and Healthcare Practice Leader for retained executive search and is the national subject matter expert for psychometric and psychological client support services. A lifetime focus on humanitarian service is reflected in Jeff’s role as the Chief Executive Officer and co-founder, with his wife Nancy, for the Hidden Value Group, an organization bringing healing, health, and hope to the world in the wake of mass disaster and violence through healthcare, education, and leadership development. They have completed more than 300 projects in 25 countries over the last 27 years. Jeff currently serves as a Subject Matter Expert, Master Teacher, Research Mentor, or Fellow in the following professional organizations: American Association of Suicidology, National Association for Addiction Professionals, The American Institute of Stress, International Association for Continuing Education and Training, American College of Healthcare Executives, and the Wellness Council of America.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.