PTSD and the Neurology of Learning

How Stress Robs Us of Understanding

This is an article from the Winter 2020/21 issue of Combat Stress

By Jeff Jernigan, PhD., BCPPC, FAIS

Gill is a 27-year-old former Army Ranger and combat Veteran. He walked into my office at the hospital one day and announced that his wife had sent him to see me; unorthodox, but effective. When I asked Gill why his wife thought I should see him, he responded with a list of her complaints: he was boring, had difficulty getting things done, especially if they involved more than just a few steps; evidently couldn’t learn from his mistakes, and couldn’t remember the last conversations they had about his changed behavior. Here is the interesting part: Gill had exited active duty nearly two years previously, had sought treatment for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder before leaving active duty, and felt the treatment was effective and that he was doing well. This was until about six months ago, when things went south in his relationship with his wife. And now he was unemployed and just as exasperated that he was getting worse, not better, as was his wife.

conversations they had about his changed behavior. Here is the interesting part: Gill had exited active duty nearly two years previously, had sought treatment for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder before leaving active duty, and felt the treatment was effective and that he was doing well. This was until about six months ago, when things went south in his relationship with his wife. And now he was unemployed and just as exasperated that he was getting worse, not better, as was his wife.

Further evaluation determined that Gill had been in multiple combat actions, suffered from a concussive head injury including brief loss of consciousness, and experienced a number of symptoms that did not go away entirely after his earlier treatment. These included difficulty in concentration, focus, memory, and decision-making, which helps explain his wife’s description of his symptoms. The oddity was her comment about him being boring and not being able to learn from his mistakes. These were; however, the most important clues of all.

Prolonged stress breaks down neural pathways, resulting in loss of concentration, focus, memory, and decision-making.1

This is true for all of us and isn’t necessarily related to PTSD. In fact, some Soldiers return from combat even stronger as a result of positive emotions, engagement with their work, a core of close relationships, meaning in their work and lives, and a sense of accomplishment.2When this is, however, associated with a closed head injury, active learning can be impaired.3 Active learning takes advantage of the cross-talk between various structures in the brain that involve how we create, evaluate, understand, and remember. These complex functions are tied to biological processes in multiple regions of the brain.4

Learning involves changing the brain. More literally, it requires the building and repair of neural pathways. For the brain to produce new brain cells (neurons), it needs stimulation. Mild stress provides the stimulation, while moderate to high stress and trauma can “lock-up” the brain due to the effects of introducing epinephrine into the bloodstream (adrenaline). That is when hyper-vigilance, elevated heart rate, and a sense of foreboding distract us from learning. In the case of closed head injury, structures in the brain can actually suffer physical injury. The process of converting perceptions into longer-term memories, a key part of learning, comes to an end. Active learning requires involvement in activities that stimulate multiple connections in the brain. If the mind is impaired due to stress and/or injury, learning does not happen.

The Stella Center, experts in helping trauma victims, followed 487 patients treated in 2017 through 2019, all diagnosed with Traumatic Brain Injuries (TBI), and found that 61percent had problems with concentration, 54 percent had problems with memory impairment, 49 percent had problems with cognition, and 25 percent had problems with mental confusion.5 This is not exactly a great learning environment inside their heads. This is the reason Gill seemed unable to learn from his mistakes and lost interest in anything that required focus or concentration. His wife’s impression was that he had slowly become a boring and forgetful husband.

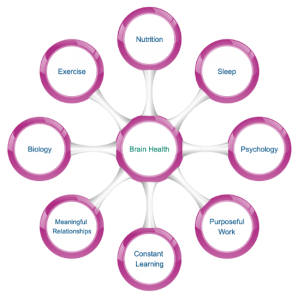

So, how do we get Gill back on his feet, active, engaged, energized, and healthy? We work on the biological and psychological sphere of his life including nutrition, exercise, sleep, and engage his brain in a therapeutic workout routine.

Beyond the basics of nutrition and brain health, there is something specific to watch out for with people who forget to eat (memory), leave the table with their meal half-eaten (focus), and because they are hungry after meals, tend to eat junk food. Too many carbohydrates, too much-processed sugars, too much red meat, and not enough vegetables can create a number of biological conditions like hypoglycemia (low blood sugar), which also mimics depression. Leaky Gut Syndrome (LGS) is another nasty byproduct of poor nutrition.6 The meats we eat often contain antibiotics fed to animals to keep them healthy. The vegetables we eat may contain toxins from the insecticides sprayed over the fields to keep insects away. These can destroy the good bacteria in the stomach needed for digestion. Over time, the lining in our intestines can break down, causing leakage into surrounding areas, which may lead to all kinds of problems.

This is important to understand. The inside of our intestinal tract is as large as three tennis courts.7 90 percent of the total number of bacteria in our body is located in our intestinal tract, along with 60 percent of our body’s total immune cells.8 Together, these form a microbiome of friendly bacteria in our body called “Gut Flora.”9 Gut Flora digests our food, neutralizes toxins, generates vitamins, creates neurotransmitters, strengthens our immune system, and protects the lining of our gut.

Antibiotics we absorb from the meat we eat kills the good bacteria in our gut. Too much sugar promotes the growth of unwanted parasitic gut microbes. Toxins from food preservatives and artificial sweeteners contribute to the deterioration of our gut lining until it is breached, releasing this chemical cocktail into our body. Poor digestion, poor vitamin production, poor neurotransmitter production, and autoimmune conditions can result. When it comes to brain health, LGS has a devastating effect. The neurotransmitters our brain needs for the various structures in the brain to talk to one another are created in our body from the food we eat. This process breaks down with LGS, killing off the good bacteria. This can shut down cognitive functions, appearing like a traumatic brain injury. Clinical depression and anxiety can result from this biological effect, as easily as it can from psychological effects.10 Gill did have problems with his diet, especially when he was left alone at home all day while his wife went to work. Not surprisingly, he was diagnosed with LGS, which was eventually resolved with a change in diet.

This brings up an interesting issue: the integration of our biology with our psychology. Mental health is not just tied to our psychology, but to our biology as well.11 It is a two-way street, the mind impacting the body and the body impacting the mind.

In Gill’s case, his physical condition (LGS) was contributing to his mental health condition and his PTSD was contributing to his physical condition. Both conditions required treatment, the goal being the restoration of a healthy brain. Our brain interactively controls everything psychologically and physiologically within us.

Exercise is key to brain health. When we exercise with some degree of intensity several times a week a protein, β-hydroxybutyrote, is produced in our muscles and travels to the brain, where it triggers the production of a Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor (BDNF).12 BDNF is crucial to learning and memory. In addition, it triggers the replacement and repair of neural pathways and brain cells.13 However, this does not happen unless you are sound asleep. This is when BDNF goes to work. Gill was exercising regularly and reported no problems with sleep disturbance.

Sleep is an important issue when dealing with PTSD. Sleep impacts safety, weight, and overall health.14 6,000 fatal car crashes a year are a result of falling asleep at the wheel. Higher levels of the hunger hormone, gherkin, and lower levels of the appetite-control hormone, leptin, lead to more cravings for sweet, salty, and starchy foods, as well as a 50 percent higher risk for obesity. Depression, irritability, anxiety, forgetfulness and fuzzy thinking are a result of sleep disturbances. Sleep deprivation can age our brains 3 to 5 years and increase our risk of dementia by 30 percent.15

Gill had not experienced another head trauma. Closed head injuries can take up to six months to a year to resolve, but he did report growing anxiety and stress over his unemployment and the resulting financial pressure on himself and his wife. Prolonged pressure over a long period of time can trigger stress-induced injuries, especially in the presence of PTSD. Gill had improved dramatically during his treatment for PTSD and thought he was cured. Unfortunately, he didn’t understand that PTSD lasts a lifetime. Though symptoms decrease over time, we have understood for a while there is always a vulnerability which remains.16 During this time, Gill also received news that a former battle buddy had committed suicide. This triggered a struggle with shame and self-blame for not being there for him, anger and grief over the loss, and further isolation from his wife and friends.

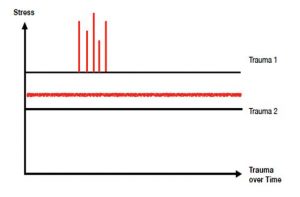

It became apparent that Gill was experiencing tremendous stress, not only from the trauma experienced in combat but from the prolonged stress of the ongoing struggle to find healing physically and psychologically. This is a situation involving Trauma 1 (a traumatic event or cluster of traumatic events) and Trauma 2 (prolonged trauma from unrelenting stress). Both types can produce the same physiological and psychological injuries to the person diagnosed with PTSD. The following chart illustrates the relationship between Trauma 1 as a cluster of traumatic events (red vertical bars) and Trauma 2 as an unrelenting ongoing lower level of stress (red fuzzy line).

If learning impairment, discussed previously, is determined to be a component of Trauma 1, it must be mitigated prior to interventions for Trauma 2. The treatment of Trauma 2 requires learning new habits, new boundaries, and new ways of being present in the moment for oneself (mindfulness). If learning has been impaired by a Traumatic Brain Injury or some other mechanism of injury, simultaneous efforts to treat Trauma 2 will be much less effective than treating them somewhat consecutively.17

Attention was also focused on Gill’s psychological health. In conversation with Gill and his wife, it became apparent Gill lacked emotional agility and the ability to connect with his wife on the level of feelings. For Gill, this was a matter of maturity. He grew up an only child and had only been married for about two years. His inability to communicate his feelings had to do with emotional intelligence, a skill that can be learned, which frustrated his wife because he seemed not to learn from his mistakes or remember the conversations they had in that regard.18 Their arguments only produced more stress and less memory. The learning part of this dynamic was something we could repair.

Gill responded well to a suggestion to get involved with a project that encompassed steps of varying complexity. He decided to build furniture since he liked working with wood. The instructions were detailed, and we encouraged Gill to refer back to the directions often and avoid worrying about forgetting something from one moment to the next. The goal was to engage his mind with complex processes that involve a greater number of neural connections and stimulate a number of areas of his brain promoting memory. In other words, this would result in reconnecting neural pathways and making new ones. Reconnection is an important part of PTSD therapy and the same structures of the brain involved in learning are also involved in reconnecting with a positive self-identity, healing from lost attachments like the loss of his battle buddy, and reconnection with friends and community.19 The key to this mind therapy was the repetitive nature of the activity. Finish one step, go on to the next one, consult the directions as often as needed. What we encounter repeatedly shapes us inevitably. The repetition was stimulating the creation of new learning pathways.

Nutrition, exercise, sleep, practicing a new skill (emotional intelligence), and repeating complex tasks brought Gill around to a place of new confidence and hope. This was ten years ago. Gill and his wife are still together, have two children, and he is enjoying a career in a US government intelligence agency, still serving his country and protecting us all.

References

- Whole: What Teachers Need to Help Students Learn, Miller; Jossey Bass, 2020; pp149-150

- Ibid

- The End of Mental Illness: How Neuroscience Is Transforming Psychiatry, Amen; Tyndale, 2020, Ch 9

- A New Model for Trauma Care: Biological and Psychological Approaches, Springer, Lynch and Okiishi; Thrive Global, June 2020

- Ibid

- Gut Health and Brain Health, Trin; Barnabas Group Keynote Presentation, Nov 2019

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Ibid

- Better Brain Health: Creating and Sustaining Resilience from Disease, Jernigan: American Institute of Stress Webinar, December 2020

- Ibid

- Exercise promotes the expression of BDNF through the action of β-hydroxybutyrote, Sleiman et al; eLife 2016; e15092; DOI 10.7554/eLife.15092, June 2016; a joint research project involving 6 universities including MIT and Harvard in the USA

- Beating Burnout, Jernigan; Keynote Presentation, Montana DSS and DMH February 2018

- Sleep Deprivation Effects; Wellness Council of America, Infographic, 2019

- Ibid

- A Clinical Handbook/Practical Therapist Manual, Meichenbaum; University of Waterloo, Department of Psychology, Waterloo, Ontario; Institute Press, September 1994

- Peer-to-Peer Recovery Coaching: Restoring and Improving Veteran Connections, with Infographic, Jernigan; American Association of Suicidology, National Task Force for Improving Veteran Access to Mental Health Resources, November 2020

- Emotional Agility in the Workplace, David; Virgin Pulse, 2018

- Warrior: How to Support Those Who Protect Us, Springer; Armin Lear Press, 2020

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jeff Jernigan, PhD., BCPPC, FAIS is a board-certified mental health professional, hospital administrator, and engineer. These describe Jeff’s 30-year career, focused on influencing change in people and organizations by capitalizing on growth and change through leadership selection and development. Jeff is the Regional Life Science & Healthcare Practice Director for Stanton Chase. Jeff’s work in life sciences, healthcare, engineering, and higher education has taken him to 38 countries around the world. As an internationally recognized thought leader and educator on the prevention of burnout and self-directed violence associated with mass violence and disasters, Jeff has also worked with military and government agencies on three continents. Jeff has been the recipient of the prestigious Workforce Optimas Award for Financial Impact, the Gallup National Healthcare Excellence Award for Culture Change, Gallup World Class Manager President’s Club Award, and the Saratoga Institute’s Global Best Practice Award for financial growth. Jeff has been featured in Healthcare Executive, Workforce, Business Finance, and Church Executive magazines for business leadership excellence; and is a Contributing Editor to Combat Stress magazine, addressing stress fatigue and PTSD in the military. Jeff is a Subject Matter Expert for stress fatigue and stress disorders with the Wellness Council of America, rated by them as one of the top one-percent of wellness experts in the country. Jeff also serves as CEO and Medical Programs Director for a major international non-profit organization providing healthcare, education, and leadership development in the wake of mass disaster and violence on three continents. As adjunct faculty or visiting professor, Jeff continues to teach the fundamentals of intervention following mass disaster and violence in National Universities in Eastern Europe, Southeast Asia, and Africa.

Jeff Jernigan, PhD., BCPPC, FAIS is a board-certified mental health professional, hospital administrator, and engineer. These describe Jeff’s 30-year career, focused on influencing change in people and organizations by capitalizing on growth and change through leadership selection and development. Jeff is the Regional Life Science & Healthcare Practice Director for Stanton Chase. Jeff’s work in life sciences, healthcare, engineering, and higher education has taken him to 38 countries around the world. As an internationally recognized thought leader and educator on the prevention of burnout and self-directed violence associated with mass violence and disasters, Jeff has also worked with military and government agencies on three continents. Jeff has been the recipient of the prestigious Workforce Optimas Award for Financial Impact, the Gallup National Healthcare Excellence Award for Culture Change, Gallup World Class Manager President’s Club Award, and the Saratoga Institute’s Global Best Practice Award for financial growth. Jeff has been featured in Healthcare Executive, Workforce, Business Finance, and Church Executive magazines for business leadership excellence; and is a Contributing Editor to Combat Stress magazine, addressing stress fatigue and PTSD in the military. Jeff is a Subject Matter Expert for stress fatigue and stress disorders with the Wellness Council of America, rated by them as one of the top one-percent of wellness experts in the country. Jeff also serves as CEO and Medical Programs Director for a major international non-profit organization providing healthcare, education, and leadership development in the wake of mass disaster and violence on three continents. As adjunct faculty or visiting professor, Jeff continues to teach the fundamentals of intervention following mass disaster and violence in National Universities in Eastern Europe, Southeast Asia, and Africa.

Combat Stress Magazine

Combat Stress magazine is written with our military Service Members, Veterans, first responders, and their families in mind. We want all of our members and guests to find contentment in their lives by learning about stress management and finding what works best for each of them. Stress is unavoidable and comes in many shapes and sizes. It can even be considered a part of who we are. Being in a state of peaceful happiness may seem like a lofty goal but harnessing your stress in a positive way makes it obtainable. Serving in the military or being a police officer, firefighter or paramedic brings unique challenges and some extraordinarily bad days. The American Institute of Stress is dedicated to helping you, our Heroes and their families, cope with and heal your mind and body from the stress associated with your careers and sacrifices.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.