Psychological Consequences of the Biden Afghanistan Debacle

By C. Alan Hopewell, PhD, MP, ABPP, MAJ (Ret), US Army

*This is an article from the Fall 2021 issue of Combat Stress

“I realized in 1973 that we were going to abandon South Vietnam and that terrible things would happen. It was beyond frustrating, deeply depressing, a stain on the nation, and there wasn’t a damn thing I could do about it. So, I worked hard to stop thinking about it and when Saigon fell, I just felt pretty numb about it. I went on with my life until many years later, when I got involved with running a charity for disabled ARVN Veterans still living in dire poverty and discrimination over there.

“Afghan Vets are now undergoing the same frustrations, sadness, and feelings of depression that most of us did back then, but they and we are now far worse off than when Saigon fell. Why? Because by the end of that time, the communist drive to take over all of Southeast Asia had worn out. The country of Vietnam was exhausted and simply needed to rebuild and China wasn’t pushing them to go anywhere anymore (to conquer more of Southeast Asia). Yes, two dominoes fell, Laos and Cambodia, but Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia were safe.

“With this victory of the Taliban, now all of jihadist Islam is strengthened, all our enemies are rejoicing, and all our allies now look at us with grave doubts. It is impossible to predict, with any accuracy, the long-term fallout of all this, but there is no doubt that the consequences are devastating ones for any civilized country. God help us. We Vietnam Veterans can only reach out if we can find a way to offer the message to Afghan War Veterans that we understand and identify with them.”1

Seeing the news of the betrayal of not only an entire country and generation of Veterans, as well as the revulsion of seeing the thousands now “left behind,” another Operation Enduring Freedom Veteran, specifically described her “visceral” reaction to the horrors unfolding in that betrayed nation. COL Kathy Platoni, Army Veteran who served with the 467th Medical Detachment (Combat Stress Control) in Afghanistan, stated emotionally that “Just seeing the images of people clamoring to get on board departing evacuation flights and falling to their deaths in the process, left her panic-stricken with the uncertainty of what would be faced by American troops, the Afghani’s who came to our aid, the interpreters, the Afghan people?”2 COL Platoni stated that during her time in Afghanistan, the Taliban were to be greatly feared and that torture and murder characterized the means by which they took revenge upon their enemies. She also stated that it was horrifying and unexpected to witness the fall of Afghanistan to the very enemy we went to war against in such rapid succession as the United States withdrew.

Such events have struck many of our Vietnam Veterans as being reminiscent of the panic and the lifelong traumata which Vietnamese survivors and Veterans confronted after that betrayed country fell to communist forces in 1973. Years of unrelenting warfare. Billions of dollars spent. Thousands of lives lost. A nation which was relatively free of the enemy and relatively stable when America transferred security operations to the national forces….all of this followed by a humiliating invasion and rapid conquest of the country, with Americans fleeing in panic, with horrific pictures of hysteria on planes and helicopters. This is what our Vietnam Veterans experienced. This is what our Afghanistan Veterans are now experiencing.

Although that war may seem to belong to a past history of long ago, over three million American Servicemen and women served in Vietnam.3 Most are still living, so easily over two million of our fellow citizens retain vivid personal memories of their service and of this betrayal. These Veterans also continue to voice the ultimate question, the same one that will remain a plague upon their lives of Veterans of the War in Afghanistan…. “Was it worth it?” This article will therefore review those similarities and shed light upon the potential psychological traumata which are expected to occur for some of the Afghan population, now also left behind in the clutches of a 7th century- minded fundamentalist religious culture ruled by jihad and terror.

COL (RET) Kathy Platoni, PsyD spent a year in Afghanistan from 2009 to 2010 leading one of several around-the-clock combat stress control clinics under the auspices of the 467th MED DET (CSC). This often led her on dangerous missions to remote parts of the country, “outside the wire.” Dr. Platoni was deployed as Officer in Charge of Team Wilson, Kandahar Province, and Camp Phoenix in Kabul, Afghanistan. With concerns over the human rights of people remaining in the country and of the safety of those who aided the U.S. in its mission, Platoni said she thinks of a man who helped the 4th Infantry Division l with whom she was embedded, as an interpreter. Not wanting to mention his name for the sake of his safety, Platoni said she worries about the “wonderful soul” who “did what he did at risk to his life and that of his family as well,” she said. “I don’t even want to think about what may become of him.”2 Platoni recalled that she worked towards assisting him in obtaining his visa for travel to the U.S. 11 long years ago, but is unsure whether he was ever able to relocate.

As a psychologist, Platoni asserted that this is a challenging time for her many clients who are Veterans. “Many of them feel betrayed that they sacrificed so much,” she said, “and that ‘everything we did was for nothing.’” Platoni recommends that Veterans who served in Afghanistan re-connect to discuss and process what they are confronting, admitting that this is “crisis time” for so many who served there over the last 20 years. She also asserts that this is because, the Taliban’s resurgence does not diminish the service that she and the thousands of other troops provided. “Our sacrifices were absolutely not in vain,” Platoni said. “We did what we did with the hope that we’d have the best outcome imaginable….and this is out of our hands. This takes nothing away from what we provided and sacrificed.”2

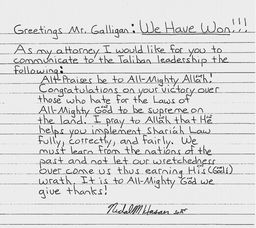

By tragic coincidence, COL Platoni’s path crossed with that of the author, MAJ [RET] C. Alan Hopewell, PhD, as he was training the 467th Medical Detachment (Combat Stress Control) in psychological and brain injury issues prior to their deployment to Afghanistan from Ft. Hood, Texas. Unfortunately, this training was cut short by the terrorist jihadist attack at Ft. Hood, which left three of the 467th dead, one in Platoni’s arms, and five wounded. The perpetrator of that attack, Nidal Malik Hasan, has now formally congratulated both the Taliban and the Biden administration for the ease in which the Taliban toppled the Afghan government and took over the country. In a letter ‘obtained’ by the Washington Examiner,4 the man who called himself a “soldier of Allah” and shouted “Allahu Akbar!” while murdering fellow troops and currently sits behind bars on death row at Fort Leavenworth, declared “We Have Won!” and congratulated Taliban leaders for their victory after 20 years of American and international forces keeping the organization out of power following the September 11, 2001, attacks. “Congratulations on your victory over those who hate for the Laws of All-Mighty God to be supreme on the land,” Hasan wrote in the letter, dated August 18th of 2021. “I pray to Allah that He helps you implement Shariah Law full, correctly and fairly.”

Both COL Platoni and the author have had extensive experience in working with both military personnel, as well as civilians exposed to horrific and extensive trauma, while performing their duties in combat theaters. The author possesses wide ranging familiarity with the post- trauma of another group of Veterans who were significantly betrayed by their country and who often felt that their service “had all been for nothing.” This is due to his first active duty assignments as an Army Clinical Psychologist shortly following the Vietnam War and as an author of a history chapter of Army Psychology5 and a book chapter on the nature of post-traumatic stress disorder.6 Traumatized survivors included not only the Vietnam Veterans who saw South Vietnam fall to communist forces, but also the frantic people who were beaten from and who fell from helicopters, in addition to the thousands of “boat evacuees.” During his deployment to Iraq in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom, the author also treated traumatized Soldiers from the 1st Cavalry Division, the 1st, 3rd, and 4th Infantry Divisions, the 10th Mountain Division, the 101st Airborne Division, and a large number of other associated and subordinate units. He also performed additional research with civilian casualties in one of the worst hit areas of the country – the “Sunni Triangle of Death.” These research efforts were further accomplished during some of the most vicious fighting in Iraq – the Battle of Sadr City.

Both COL Platoni and the author have been struck by the similarities between all of these groups: Vietnam Veterans who felt betrayed when South Vietnam fell to an enemy when this was completely preventable, Soldiers who fought in the current Global War on Terrorism are now witnessing an almost identical catastrophic debacle and civilians and native citizens who worked for American forces, such as interpreters, among other dedicated Afghans, were also abandoned and betrayed.

Two groups in particular, which can be compared to our current troops and civilians in Afghanistan, were studied intensively prior to the fall of that country. The trauma experienced by these two groups are directly comparable to what both Soldiers and civilians are experiencing this very moment in the debacle still occurring in Afghanistan. The first group included active duty Soldiers, primarily from the 1st Cavalry Division and the 4th Infantry Division, both of which had been deployed from Ft. Hood Texas between the years 2006 through 2010. The second group included Iraqi civilians and some military interpreters who had been subjected to similar horrors of war and who were evaluated during a March 2008 MEDCAP mission in Mahmudiyah, Iraq.7 These military civic action programs are types of military operations which are designed to assist a wore torn area by using the capabilities and resources of a military force to conduct long-term programs or short-term projects for medical or civil aid. These types of operations generally included: dental civic action programs (DENTCAP), engineering civic action programs (ENCAP), medical civic action programs (MEDCAP), and veterinarian civic action programs (VETCAP). The U.S. military will normally conduct these types of operations at the invitation of a host nation.8

In June of 2006, the author, after volunteering to return to active duty for the War on Terror, assumed his duties as the Officer in Charge of what turned out to be the largest psychiatric outpatient clinic in the world at the time (The Resilience and Restoration Center at Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center at Ft. Hood Texas.) At the direction of the Hospital Commander (COL and later BG Lorree Sutton,) the author conducted PTSD and brain injury surveillance and research on returning combat Veterans, generally those who served in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF). This eventually included more than 6000 combat Veterans at Ft. Hood.9,10 While in Iraq as support of the Surge of U. S. forces from 2007 to 2008, the 785th Medical Detachment; 56th Medical Battalion (Combat Stress Control) saw more patients en total than any other Combat Stress Unit during OIF (COL Robert Evans, personal communication, 2010).

In the context of the Iraq War, the Surge referred to United States President George W. Bush‘s 2007 increase in the number of American troops in order to provide security to Baghdad and Al Anbar Governorate.11 In response to continuing unrest in Iraq, President Bush ordered the deployment of more than 20,000 soldiers into Iraq (five additional brigades), and sent the majority of them into Baghdad.12 The President described the overall objective as establishing a “unified, democratic federal Iraq that can govern itself, defend itself, and sustain itself, and is an ally in the War on Terror.”13 The major element of the strategy was a change in focus for the US military “to help Iraqis clear and secure neighborhoods, to help them protect the local population, and to help ensure that the Iraqi forces left behind are capable of providing the security.”14 The President stated that the Surge would then provide the time and conditions conducive to reconciliation between communities.

As the name designated Traumatic Brain Injury Consultant, Multinational Force, Operation Iraqi Freedom, the author conducted in-country research on an additional 2000 to 3000 wounded Soldiers as well as the aforementioned MEDCAP mission, the latter of which took place in Mahmudiyah in the renowned “Sunni Triangle of Death.”7 “Name designated” means that the author was designated by name by the Multinational Force, Operation Iraqi Freedom, in coordination with the U.S. Army Psychology consultant COL Bruce Crow, to be the Traumatic Brain Injury Consultant during the author’s tour of duty in Iraq. The “Sunni Triangle of Death” was the area widely known as one of the most dangerous areas in all of Iraq. This was the description given to a rural area south of Baghdad which was marked by a rough geographical triangle and which included the three “triangle” cities of Yusufiyah, Latifiyah and Mahmudiyah. For example, when the U.S. Marine Corps 2nd Battalion entered Yusufiyah in the middle of September 2004, one of the first things they laid eyes upon was an Iraqi police officer hanging from a tree. There was a sign hanging from him indicating that “This is what happens when you help U.S. Forces.” Similar sights may already be underway throughout Afghanistan, and reports of savage executions and retribution have already begun to surface.15

Because of the fighting in and around the “Triangle of Death,” the area was targeted for special assistance during the 2008 Surge. The primary unit stationed in the area was the 3-320th Field Artillery Unit. This unit was supported by a field clinic from the 785th Medical Combat Stress Company, with CPT Jeffrey Greenlinger, MSC, Social Worker, as Officer in Charge (OIC). As a result of the intense fighting and atrocities committed in this area, the Commander of the 3-320th Field Artillery requested specific research involving trauma experienced by the local Iraqi population so that he could work more effectively with them. For this project, the author flew to Mahmudiyah to coordinate a MEDCAP mission and for the requested data collection for research. The mission was coordinated with CPT Greenlinger, SSG Jay Harbeck, and SGT Jeremy White of the 785th.

785th Combat Stress Unit at Mahmudiyah, Iraq, March 2008.

However, as the MEDCAP mission was about to move out, on 25 March 2008, an ‘Iraqi military assault’ was launched against the port city of Basra, which was held by a number of militia groups, primarily by the Mahdi Army. This led to the collapse of the cease-fire and renewed fighting in Sadr City in Baghdad itself. Beginning early in the morning of March 25th, the Mahdi Army militia launched a number of rocket and mortar attacks from Sadr City at US ‘forward operating bases’ throughout Baghdad, as well as the ‘Green Zone.’

The 2008 Battle of Sadr City involved approximately six weeks of intensive fighting, not all of it confined to the Baghdad area. The battle ultimately resulted in the coalition’s defeat of Jaish al-Mahdi. The battle also spread to other areas such as the “Triangle of Death.” In Mahmudiyah, night fighting continued when U.S. units there were attacked with small-arms, machine guns and RPGs (rocket-propelled grenades). Snipers and roadside bombs were also used against coalition convoys. Because of this, the scheduled MEDCAP was terminated prematurely and the author and his Sergeant were evacuated by Blackhawk back to Camp Liberty. About one month later, CPT Greenlinger, SSG Jay Harbeck, and SGT Jeremy White of the 785th were able to complete the MEDCAP mission and collect the final data involving 75 Iraqi civilians, including 31 children.

Vehicular damage, 3-320th Field Artillery, Mahmudiya, March 2008.

In addition to demographic and other routine medical information collected through the MEDCAP mission, the Traumatic Event Sequelae Inventory (TESI) was translated into Arabic and administered to 75 Iraqi civilians attending the MEDCAP. The Traumatic Event Sequelae Inventory is a special psychometric instrument, designed to diagnose and quantify a very specific emotional and behavioral symptom spectrum most frequently reported by individuals who have been exposed to one or more traumatic events. TESI was developed in 1995 as a focal component of a comprehensive, multidimensional psychometric battery for assessment and quantification of emotional injury and psychiatric disability.16 Originally intended for the commercial market only (personal injury/workers’ compensation), the first announcement about TESI appeared in the California CLAIMS Journal, Winter 1996. Since then, TESI has become the most widely used instrument in the USA for assessment of posttraumatic emotional and behavioral sequelae.16 Scores range from a gradient frequency score of 1 (minimal or no trauma) to 8 (most severe trauma). During the 3-320th Field Artillery research, the results of the Arabic TESI administrations were compared with norms from over 64,000 U.S. PTSD/ trauma cases, and more than 6000 Soldiers diagnosed with both PTSD and concussive injuries. Most of these were Iraq War Veterans. The sequelae of both PTSD and concussive injuries have been well delineated in Moore, Hopewell, and Grossman, (2009).

The author at Mahmudiyah, Iraq, March 2008

The results of the MEDCAP research demonstrated that overall, the Iraqi civilians in the Mahmudiyah area had the most severe problems with fear, psycho acceleration (hyperactivity or arousal,) anxiety, ruminations, anger, musculoskeletal pain, disrupted ability to function in everyday life (ADLS) and both Criteria A and D of the PTSD diagnosis. They scored the highest on PTSD measures of re-experiencing trauma and increased arousal, with lower scores on avoidance, social impairment, marital disturbances and digestive problems. In addition to expected mood disturbances, cognitive, marital, occupational, general functional, and dissociative symptoms were all reported as severe. A summary of the TESI primary disturbances are detailed below.

Hopewell, C. A., Greenlinger, J., Harbeck, J, and White, J. (2008). Psychological Trauma of Local Population in Mahmudiyah Area. Presented to 3-320th FA, FOB Mahmudiyah, Iraq.

The mean scores of the Iraqi civilians were between the 7-8 range on the TESI. Religion and family were the main resources for emotional support. As is the case for PTSD in general, symptoms were more prevalent in women than men.17 When compared to the combat Veterans evaluated at Ft. Hood, scores of these Iraqi civilians were uniformly more severely elevated.18

The bottom line was that the Iraqis seen in this area of constant strife and terrorist attacks were more traumatized than U.S. combat Veterans with injuries, such as traumatic brain injuries combined with PTSD.

So, what do the memories of Vietnam Veterans brought about 50 years ago and traumatized Iraqis have to do with the current situation in Afghanistan? First of all, lessons learned from our Vietnam Veterans tell us that memories of sacrifice and betrayal are incredibly destructive at the very base of the soul, and that such memories not only do not go away but may even become increasingly painful over time. Lessons learned also tells us that the underlying mistrust of the government involved in such betrayal may also persist for a lifetime and never subside, with an overriding questioning of “was my sacrifice, and that of my brothers and sisters worth it?” These are more than likely to be the same feelings occurring with our current Veterans; ones that will probably remain with them for the rest of their lives.

And what do the results of a MEDCAP mission done in a little known and remote town in Iraq tell us? Lessons learned also tells us that civilians traumatized in these ways will be scarred for the remainder of their lives, and in some cases, the trauma can be even worse than that involving military personnel who have been neurologically injured and psychologically traumatized by being “blown up.” Such sufferings will probably never resolve completely, and the consequences of PTSD at this level of severity almost always includes large numbers of co-morbid disorders and a shortened life span.17

What are some other problems that we can foresee from a humanitarian perspective as well as the devastating manmade disaster underway in Afghanistan? COL Platoni and the author were not only U.S. Army Officers, but psychologists charged with motivating Soldiers and “Conserving the Fighting Force.” How do we or any of our fellow military psychologists now encourage young people to join the Armed Forces? How do we motivate troops who may be discouraged, tired, and worn out by multiple deployments?19 How do we counsel potential career troops on their military careers? How do we counsel those who have been injured in the line of duty, of the families of the dead or injured? How do we counsel retirees and Veterans, all of whom may feel now that “MY SERVICE WAS NOT WORTH IT, AND MY COUNTRY AND MY MILITARY LEADERS WILL NOT SUPPORT ME?”

These are the questions that only can be answered in the future by a nation and military leaders who are either committed to duty, honor, and country, or who are not.

References

- Del Vecchio, R. J. (2021). Personal communication. Combat Photographer 1st Marine Division 1968. Secretary, Vietnam Veterans for Factual History, vvfh.org,Board Chairman, Vietnam Healing Foundation, www.thevhf.org.

- Platoni, K. T. (2021). Personal communication. COL, USA [RET].

- S. Department of Veterans Affairs. (2021). Military Health History Pocket Card. https://www.va.gov/OAA/pocketcard/m-vietnam.asp. 21 September 2021.

- Browne, P. (2021). Fort Hood gunman congratulates Taliban from death row in handwritten letter. Washington Examiner, 8 September 2021.

- Hopewell, C. Alan (2013). History of Military Psychology. In Military Psychologists’ Desk Reference. Bret Moore and Jeffery Barnett. (Eds). Oxford University Press, New York.

- Bret A. Moore, C. Alan Hopewell, & Dave Grossman, (2009). Violence and the Warrior. In Living and Surviving In Harm’s Way: A Psychological Treatment Handbook for Pre- and Post-Deployment. S. M. Freeman B. A. Moore, and A. Freeman, (Eds.) Routledge: New York.

- Hopewell, C. A., Greenlinger, J., Harbeck, J, and White, J. (2008). Psychological Trauma of Local Population in Mahmudiyah Area. Presented to 3-320th Field Artillery, FOB Mahmudiyah

- Chairman, U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, Joint Doctrine for Civil-Military Operations, Joint Publication (JP) 3-57 (Washington, DC: CJCS, February 08, 2001), p. I-24.

- Christopher, R. and Hopewell, C. (2007) Comparative analysis of traumatic sequelae between Iraqi civilian population and US military personnel. ISBN 1-58028-168-0. Reno, Nevada: Psychological, Clinical, and Forensic Assessment.

- Christopher, R. and Hopewell, C. (2007) Quantitative analysis of military trauma symptomatology. ISBN 1-58028-167-2. Reno, Nevada: Psychological, Clinical, and Forensic Assessment.

- Duffey, M. (2008). “The Surge at Year One.“ Time, January 31, 2008.

- Feaver, P. (2015). Hillary Clinton and the Inconvenient Facts About the Rise of the Islamic State Foreign Policy, (August 13, 2015).

- United States Senate Committee on Armed Services. Benchmarks: Hearings Before the Committee on Armed Services, United States Senate, One Hundred Tenth Congress, First Session, September 7 and 11, 2007, Volume 4, U.S. Government Printing Office, Jan 2008, page 297.

- Israel, Fred L. and McInerney, Thomas J. Presidential Documents: The Speeches, Proclamations, and Politics That Have Shaped the Nation from Washington to Clinton, Routledge, 2013, page 374.

- Limaye, Y. (31 August 2021). Amid violent reprisals, Afghans fear the Taliban’s ‘amnesty’ was empty. BBC News.

- Christopher, R. (1997). What is “TESI?” Professional, Clinical and Forensic Assessments, LLC (PCFA).

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual V. (2013). American Psychiatric Association. Washington, DC.

- Christopher, R. and Hopewell, C. A. (2007) Psychiatric correlates of combat trauma in military personnel: PTDS and TBI TESI statistical analysis. Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom. ISBN 158028-16-4. Reno, Nevada: Psychological, Clinical, and Forensic Assessment.

- Hopewell, C. Alan & Denise Horton, (2012). The Effects of Repeated Deployments on Warriors and Families, In When the Warrior Returns, Nathan D. Ainspan and Walter E. Penk. (Eds). Naval Institute Press: Annapolis, Maryland.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Hopewell Holds four degrees and four foreign language certifications, to include his BS, MS and PhD in Clinical Psychology and a second Master of Science Degree in Clinical Psychopharmacology.

He Received his formal Clinical Neuropsychological training during his residency at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston in the Division of Neurosurgery where he was the very first student of Harvey Levin, PhD, ABPP

Dr. Hopewell was commissioned upon his graduation from the Texas A&M Corps of Cadets. He has served as Chief of Psychology Service at Landstuhl Army Regional Medical Center, where he founded the initial Traumatic Brain Injury Laboratory and at Brooke Army Medical Center, among others. He was the first Army Officer Prescribing Psychologist to serve and to practice in a Combat Theater, where he was awarded the Bronze Star Medal for meritorious service during Operation Iraqi Freedom. He was subsequently awarded a Meritorious Service Medal as he was a primary target during the Ft. Hood Jihadist Terrorist attack by his colleague, Nidal Hasan.

A former President of the Texas Psychological Association, he was also Awarded the Texas Psychological Association Award as the Outstanding Clinical Neuropsychologist in Texas.

He is currently Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine, University of North Texas Health Science Center and maintains his practice in Fort Worth. He has been married for 48 years, has two sons, and is just now expecting his first grandson. His father, LTC Clifford Hopewell, a B-17 navigator prisoner of war, was the stenographer for the infamous Stalag Luft III prison camp in Germany (The Great Escape).

Based upon his combat service and as a prescribing psychologist, he was awarded one of the highest honors of the American Psychological Association, being elected a Fellow of the APA. He is currently an Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine at the University of North Texas Health Science Center.

Combat Stress Magazine

Combat Stress magazine is written with our military Service Members, Veterans, first responders, and their families in mind. We want all of our members and guests to find contentment in their lives by learning about stress management and finding what works best for each of them. Stress is unavoidable and comes in many shapes and sizes. It can even be considered a part of who we are. Being in a state of peaceful happiness may seem like a lofty goal but harnessing your stress in a positive way makes it obtainable. Serving in the military or being a police officer, firefighter or paramedic brings unique challenges and some extraordinarily bad days. The American Institute of Stress is dedicated to helping you, our Heroes and their families, cope with and heal your mind and body from the stress associated with your careers and sacrifices.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.