Acute stress disorder can develop following a person’s exposure to one or more traumatic events. Symptoms may develop after an individual either experiences firsthand or witnessed a disturbing event involving a threat of or actual death, serious injury, or physical or sexual violation. Symptoms begin or worsen after the trauma occurs and can last from three days to one month.

Acute stress disorder can develop following a person’s exposure to one or more traumatic events. Symptoms may develop after an individual either experiences firsthand or witnessed a disturbing event involving a threat of or actual death, serious injury, or physical or sexual violation. Symptoms begin or worsen after the trauma occurs and can last from three days to one month.

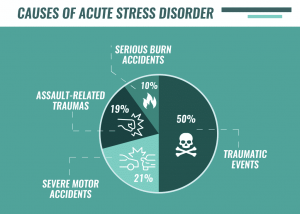

It is estimated that between 5 and 20 percent of people exposed to trauma such as a car accident, assault, or witnessing a mass shooting develop acute stress disorder. And approximately half of those go on to develop post-traumatic stress disorder.

The diagnosis of acute stress disorder was established to identify those individuals who would eventually develop post-traumatic stress disorder. The condition was referred to as “shell shock” as far back as World War I, based on similarities between the reactions of soldiers who suffered concussions caused by exploding bombs or shells and those who suffered blows to their central nervous systems. More recently, acute stress disorder came to recognize that people might exhibit PTSD-like symptoms for a short period immediately after a trauma.

Trauma has both a medical and a psychiatric definition. Medically, trauma refers to a serious or critical bodily injury, wound, or shock, and trauma medicine is practiced in emergency rooms. In psychiatry, trauma refers to an experience that is emotionally painful, distressful, or shocking, often resulting in lasting mental and physical effects.

In general, it is believed that the more direct the exposure to a traumatic event, the higher the risk for mental harm. Thus in a school shooting, for example, the student who is injured will likely be the most severely psychologically affected, and the student who sees a classmate shot or killed is likely to be more affected than the student who was in another part of the school when the violence occurred. Even secondhand exposure to violence can be traumatic. For this reason, all children and adolescents exposed to violence or a disaster, even if only through graphic media reports, should be watched for signs of emotional distress.

Symptoms

Symptoms

Acute stress disorder is diagnosable when symptoms persist for a minimum of three days and last no more than one month after a traumatic experience. If symptoms persist after a month, the diagnosis becomes post-traumatic stress disorder.

According to the DSM-5, acute stress disorder symptoms fall into five categories:

• Intrusion symptoms—involuntary and intrusive distressing memories of the trauma or recurrent distressing dreams

• Negative mood symptoms—a persistent inability to experience positive emotions, such as happiness or love

• Dissociative symptoms—time slowing, seeing oneself from an outsider’s perspective, or being in a daze

• Avoidance symptoms—avoidance of memories, thoughts, feelings, people, or places associated with the trauma

• Arousal symptoms—difficulty falling or staying asleep, irritable behavior, or problems with concentration

People with acute stress disorder may also experience a great deal of guilt about not having been able to prevent the trauma, or for not being able to move on from the trauma more quickly. Panic attacks are common in the month following a trauma. Children with acute stress disorder may also experience anxiety related to their separation from caregivers.

Causes

A person must be exposed to a traumatic event to be at risk for acute stress disorder. It is not clear why only a small proportion of people exposed to develop a stress disorder. Individuals may be at greater risk for developing stress disorder if they have previously been diagnosed with a mental disorder, perceive the traumatic event to be very severe, have an avoidant coping style when experiencing distress, or have a history of previous trauma. Women are more likely to develop acute stress disorder than men.

The body has a built-in, physiological response to acute stress—the stress response. When a fearful or threatening event is perceived, the body engages an automatic response geared toward either confronting the threat, freezing up, or fleeing the threat (hence the term “fight-flight-freeze response”). The hallmarks of the acute stress response are an almost instantaneous surge in heart rate, blood pressure, sweating, breathing, and metabolism, and a tensing of muscles. Enhanced cardiac output and accelerated metabolism are essential to mobilizing for action. Psychologically, attention is concentrated on the threat. After people experience a trauma, they may be more vigilant for new threats and perceive constant threats in their environment based on assumed danger (due to intrusive memories or dreams, for example), and therefore experience the acute stress response more frequently than before.

Treatment

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is the treatment that has met with the most success in combating acute stress disorder. CBT has two main components. First, it aims to change cognitions or patterns of thought surrounding the traumatic incident. Second, it tries to alter behaviors in anxiety-provoking situations. Cognitive behavioral therapy not only ameliorates the symptoms of acute stress disorder but also attempts to prevent the development of post-traumatic stress disorder.

Psychological debriefing and anxiety management groups have also been examined for the treatment of acute stress disorder. Psychological debriefing involves an intense therapeutic intervention immediately after the trauma so that traumatized individuals can “talk it all out.” While some people have found such intervention to be helpful, others have been re-traumatized by speaking about the situation that originally caused them distress.

Psychotropic medications can assist with symptoms of anxiety and high arousal. Additionally, stress-reduction strategies, such as mindfulness and relaxation techniques, can help people cope with and ultimately reduce symptoms of acute stress disorder, and prevent future occurrences of acute stress disorder.

References

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. American Psychiatric Association.

- Barlow, D. H. (2004). Anxiety and its disorders: The nature and treatment of anxiety and panic. Guilford Press.

- Jones, F. D., Sparacino, L. R., Wilcox, V. L., Rothberg, J. M., & Stokes, J. W. (1995). War psychiatry, textbook of military medicine. Zajtchuk, Bellamy & Jenkins (Eds.), Office of the Surgeon General.

- National Institute of Mental Health

- National Center for PTSD

- Department of Health & Human Services

- Center for the Study of Traumatic Stress

Last reviewed 02/07/2019 Original Article: HERE